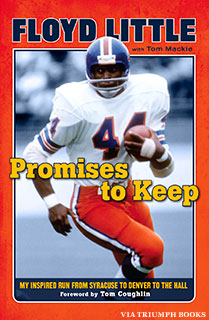

Floyd Little was raised in poverty in New Haven, Connecticut. He was bowlegged, sent off to military school and told his IQ was too low to even consider college. He overcame those obstacles to become a three-time All-American football player at Syracuse and one of the best NFL running backs of his era with the Denver Broncos. After football, he earned a law degree and ran a successful automobile dealership for more than 25 years. In Promises to Keep, Little reflects on a lifetime of beating the odds and achieving excellence on and off the field. He shares his memories from his record-setting seasons at Syracuse and in Denver and reflects on his long, unconventional road to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Here is an excerpt:

In the movie The Express, just before Ernie Davis walks out of the tunnel and onto the football field for the last time as a member of the Cleveland Browns, Ben Schwartzwalder walks up to Davis and says, "Ernie, I don't know what you said to Floyd Little, but he's coming to Syracuse." It was an emotional conclusion to a great movie. When you watch the film you can see why they scripted it that way. But in real life it happened differently.

I was on winter break from Bordentown on a snowy night in December 1962. I had just returned to my home in Connecticut after taking the Army's strenuous endurance test at West Point. Another recruit, Dave Rivers, who eventually became Army's captain, and I were put through a series of endless physical endurance tests that included pull-ups, sit ups, rope climbing, sprints, and long-distance running. We were so drained by the end that I could barely stand, and Dave was practically out cold. I felt like it was going to take me a year to recover. Somehow I managed to break all the endurance records set years before by Doc Blanchard and Glenn Davis, the original Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside.

I wasn't home for more than an hour when the doorbell rang. A blanket of snow had covered the region, and the darkness was barely illuminated by the pristine snow. I opened the door and there stood a short white man with gray hair and glasses, Syracuse football coach Ben Schwartzwalder. Next to him were two assistants. The three men parted like Secret Service agents, and standing behind them was this tall handsome man wearing a fine camel-haired coat. He was stacked up better than dirty laundry. Ernie Davis. My sisters were practically pawing at him through the door. "Who is that?" they kept whispering behind me. It was as if as Elvis Presley was at our doorstep.

You can't imagine people like that coming to our neighborhood at that time of night. It seemed as if Ernie was more like their escort. The four men introduced themselves and asked me if I wanted to go to dinner. Well, in my house, a free dinner was like hitting the lottery. On top of being exhausted, I was starving. So they took me to Jocko Sullivan's, a nice bar and grill restaurant on the campus of Yale University. It wasn't every day that I was chauffeured to a fine restaurant, so I kept pinching myself underneath my coat.

At the restaurant my main concern wasn't talking football, it was eating. I had already finished reading the entire menu from front to back. I didn't know what steak or lobster looked like. So I was going to order one of each. Then right after we ordered, Ernie tapped me on the shoulder and said, "Let me talk to you for a minute." And I'm thinking to myself, Before I eat? So I got up and followed him. Of all places we head into the men's room. He goes in and puts one foot up on the urinal and looks at me. Well, I always wanted to be like Ernie, so I put one foot up on the urinal just like him. We looked like we were holding fort at the OK Corral. We sat and talked for about 45 minutes, right there in the men's room.

He said to me, "I hear you're a real good football player." I said, 'Well, I'm not a bad player." He said, "I hear you've got a lot of scholarship offers." I said, "Yeah, 47 of them." He said, "Let me tell you a little bit about Syracuse." I'm all ears. I mean, here's Ernie Davis, the first African American to win the Heisman Trophy, who just signed a contract with the Cleveland Browns for big money, like $100,000. He also just signed another $100,000 contract with Pepsi. And here I used to cash my checks at the 7–Eleven.

Ernie told me, "They got a football coach up there who likes to run the football. He doesn't like to pass. His philosophy is that three things happen when you pass the ball and two of them are bad. They can catch it and you can drop it. Not good. At Syracuse you'll be running the ball. But more important, they care about your education. They want you to go to class. They're concerned if you miss class because they want you to graduate. Even if you decide you don't want to play football anymore, you'll still keep your scholarship. That's one of the most important things about Syracuse."

So I started thinking about all those scholarships I was offered -- football scholarships. This was more like an academic scholarship. I didn't know how smart I was, but with the help of Syracuse, the faculty, and all their support, they could help me through this all. I said, "Ernie, this sounds good. I'll go to Syracuse." I told him I would go, but I was still leaning toward Army and Notre Dame. For one thing I hadn't eaten yet, and I could always claim light-headedness.

Months passed and I still hadn't decided. Then I got this phone call from someone who told me Ernie Davis had died. I said, "Ernie Davis, the Heisman Trophy winner?" He told me, "Yes." I was like, "How could he die, he's only 23 years old?"

He told me Ernie had some rare blood disease called leukemia. I was shocked. I started thinking, My God. I promised him I would go to Syracuse. I hung up the phone and sat there as this incredible flow of emotion poured out of me. I couldn't believe such an incredible man with such a bright future was gone. I had given Ernie my word that I would go to Syracuse. To me, my word is my bond. It defines who I am. I couldn't go back on my word. Right then, I knew what I had to do. I picked up the phone and called Ben Schwartzwalder. "Coach," I said, "I'm coming to Syracuse."

Ernie Davis had that kind of effect on so many people. I wanted to continue that legacy. I wanted to go to Syracuse to be the kind of player he was and the kind of player he could have been in the pros. More importantly, I aspired to be the kind of man Ernie was off the field -- to carry on the tradition that Ernie had asked me to fulfill. He wanted me to wear 44 like he had and Jim Brown before him. He told me Jim did okay there, he did fine, and so would I.

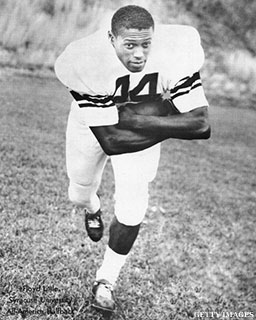

When I got to Syracuse and was given 44, the same number worn by Ernie and Jim Brown, I was determined to live up to their legacy. I was a huge Jim Brown fan. But Ernie is the person I wanted to pattern myself after. He never had a chance to fulfill his dream and live a long life. So I tried to be the man Ernie didn't get the chance to be. I wanted to live the life Ernie should have been given. If they associated me with the kind of person Ernie was, that was a good thing.

When I put on the No. 44 jersey for the first time, I didn't set out to rush for more yards than Jim and Ernie. Just being part of that legacy was good enough for me. What a tremendous honor! Jim Brown is the greatest player to ever step onto the football field. Ernie Davis was a trailblazer, the first African American to win the Heisman Trophy. Because of those two men, I always played as hard as I could in college. Of course, that was my mentality on every level. But in college, I played as hard as I could because I wanted to continually honor the No. 44.

Although Ernie Davis had promised me number 44, it wasn't guaranteed. Unlike today where freshman are eligible to play varsity, I spent my first year at Syracuse in 1963 playing on the freshman team. I must have made an impression on the coaching staff because when I showed up at my first varsity practice in 1964, I was given No. 44. To wear the number and follow in the footsteps of the great Jim Brown, my idol growing up, and the incomparable Ernie Davis well, it was beyond a dream come true. I instantly became part of football history.

In 2005, during Syracuse's Homecoming game against South Florida, Syracuse finally retired No. 44. It now sits in the rafters of the Carrier Dome. I was there for that unforgettable weekend culminating in the halftime retirement ceremony where Jim Brown, Ernie Davis's mother, Marie Fleming, and other great players including Bill Schoonover, Michael Owens, Rob Konrad, and I were each given a replica No. 44 jersey and helmet from our playing days. My family and friends were there, including my grandson, Blaze Kennedy Jones, to whom I gave my jersey and helmet. I've been told that the university may un-retire the jersey for special occasions. One of them will be when Blaze goes to Syracuse and plays tailback for the Orange. He'll wear his Poppy's number proud. I'm 70 years old, but I'm eating right and staying in shape in hopes that I'll be around to see Blaze wear No. 44.

-- Excerpted by permission from Promises To Keep by Floyd Little with Tom Mackie. Copyright (c) 2012 by Floyd Little with Tom Mackie. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.