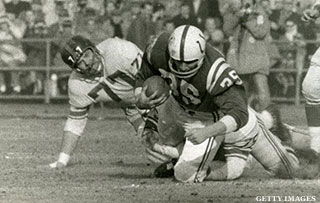

Born in 1933 to Italian immigrants, Alan Ameche grew up in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and went on to break Big Ten rushing records for the Wisconsin Badgers, leading them to the 1953 Rose Bowl and winning the 1954 Heisman Trophy. He earned his nickname "The Horse" for his tremendous training ethic, power, and stamina. In a professional career with the Baltimore Colts that lasted just six seasons before injury ended it, he was the 1955 NFL Rookie of the Year and went to the Pro Bowl five times. The 1958 NFL championship game pitted Ameche's Colts against the New York Giants in what has often been called the "Greatest Game Ever Played." Ameche scored in overtime to give Baltimore its first NFL championship. This excerpt of Alan Ameche: The Story Of The Horse by Dan Manoyan reveals that his career with the Colts wasn't always so smooth.

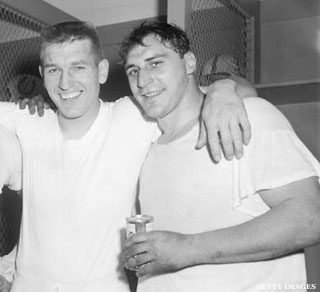

Ordinarily, Gino Marchetti probably never would have remembered the first time he laid eyes on Alan Ameche. But fifty-six years after the fact, he still remembers the moment with crystal clarity because of the conversation that accompanied the sighting.

"It was really strange," said Marchetti, the Baltimore Colts Hall of Famer and arguably the greatest defensive end ever to play in the NFL. Marchetti was a World War II veteran who was a machine gunner at the Battle of the Bulge and would later in life be Ameche's business partner.

"I remember it was before camp opened, and I was walking with [Colts coach] Weeb Ewbank. We were coming from a meeting and heading to chow, and Alan was walking ahead of us.

"I remember it because Weeb made a really strange comment that stuck with me over the years. He sees Alan in front of us and he says, 'There is our big draft choice. He was babied in college. He was spoiled at Wisconsin. They didn't baby you in college, did they Gino?' Weeb asked me. I told him, ‘No, I wasn't babied.'"

It might have only been a first impression, but apparently for the inflexible Ewbank, it was his lasting impression of Ameche. Despite what Ameche would accomplish on the field for the Colts, and his feats were borderline Hall of Fame caliber, Ewbank would ride him mercilessly and, eventually, right out of the league. It's safe to say that the feelings between the two men were mutual, and that animosity ruined what should have been six of Ameche's happiest years on Earth.

"It was so strange because here Weeb hadn't even had a chance to know the guy and he'd already made up his mind about him," Marchetti said. "The really strange thing is that Weeb never changed his mind about Alan. He never, never liked Alan for some reason, and I never could figure it out.

"Alan worked hard, he played hard, he was a good blocker. He did everything that was asked of him, but Weeb would never give the guy a break.

"The only thing I can think of is one thing. Alan had a habit of always being barely late for everything ... meetings, practice, pregame meals. Things like that really bothered Weeb. Alan would come out to practice sometimes with his shoes untied and he'd have to bend over to tie them up on the field. All of those things bothered Weeb and put a strain on their relationship."

The Ameche-Ewbank feud was common knowledge among Colts insiders, and it really was an anomaly. To a man, the Colts will tell you that there was a genuine camaraderie on the squad. Like every team, the players came from all walks of life, but this was a group that genuinely practiced and believed in the team concept.

"I know that Weeb had an attitude toward Alan, and to this day I don't understand it," said another Ameche friend and Hall of Fame wide receiver, Raymond Berry. "I have my theories about it, but I honestly don't know for sure.

"There is no question that Weeb's attitude toward Alan was not good and not healthy for the team, and in the long run it proved costly to the Baltimore Colts and Weeb Ewbank.

"Alan came in here as Heisman Trophy winner and he had a personality that was very extroverted, and he had a tremendous sense of humor and laughed a lot. I think maybe Weeb took that as not caring or being too lackadaisical, but that just wasn't the case.

"Alan's personality gave the appearance of being very loose, but I think that is misleading. Weeb was blind to Alan's productivity as a player. That's all he needed to judge Alan, or any player for that matter, but Weeb took it way beyond that.

"I'm sure Alan got a good bonus for signing a contract, and Weeb probably didn't like that either. I think Weeb thought Alan was paid too much and he had too much hype and reputation.

"There was just something about Alan Ameche that Weeb did not like. Whatever it was, it was so counterproductive it was unbelievable."

Ewbank may have won the battle with Ameche. In 1960 Ewbank effectively drove Ameche off the squad by making it clear that he was not wanted back after rehabbing his Achilles tendon injury. But the bottom line was that Ewbank's unfounded dislike for Ameche cost him and the Colts more than it hurt Ameche.

"The end result was, I believe, it cost Weeb his job," Berry said. "You know Weeb lost his job two years after Alan retired, and the reason was we got overbalanced throwing the ball. We really didn't have an effective running game after Alan retired.

"I don't know if Alan would have ever recovered from the Achilles tendon injury or not, because that injury was pretty uncommon those days, so there wasn't a lot of medical experience to go by in dealing with that injury. I just know that our offense totally changed from the time we lost Alan Ameche, and two years later Weeb got fired himself because he couldn't put a balanced attack on the field.

"We became overly reliant on Unitas throwing the football. You get out of balance in the NFL and your butt is going to get handed to you. You'd better be able to run and throw and hurt people on the ground and in the air. We got to the point where we couldn't hurt them on the ground, so they pinned their ears back and took their pass rush to another level.

"When opponents are teeing off on your quarterback, obviously it affects your passing game. We struggled to be a contender after Alan retired."

Berry went on to have a very solid coaching career after his Hall of Fame playing days were over, coaching the New England Patriots from 1984 through 1989, including Super Bowl XX in 1986, and it's for certain that his role model for dealing with players wasn't Ewbank. Berry believed that Ewbank had picked up the destructive habit of needling his players when he was the offensive line coach on the staff of Paul Brown, the legendary coach of the Cleveland Browns.

"I think Weeb was influenced very much as a young coach working under Paul Brown," Berry said. "I don't think there is any question about that.

"And Paul Brown had a habit of needling his players; this was well known about him. He would needle his players with barbs and comments and verbal shots. Then Weeb comes to the Colts, and I know he was affected by Paul Brown's operation.

"I saw that myself, his need to needle players. My rookie year I was definitely on Weeb's list. I thought the needling was very counterproductive and to be honest, it hurt Weeb in his relationship with his players.

"I mean you can mark that down. That's exactly a big part of what was happening. Alan was on the receiving end of it. There is no question that he took a lot of needling from Weeb."

Art Donovan played next to Marchetti in the Colts' defensive line for years and like Marchetti and Berry is an NFL Hall of Famer. Donovan thinks there might be more to Ewbank's dislike of Ameche than the fullback's tendency to be tardy.

"To be honest with you, I don't think Weeb liked anybody who made more money than he did," Donovan theorized. "Weeb never liked the Horse from the beginning and it was because the writers were writing more about the Horse than they were about him.

"Don't get me wrong, Weeb was a helluva coach. ... He had a great football mind. But he was a downright weasel. He thought he was something, and it was a lie from the beginning. But you better believe it ... we all knew.

"How somebody couldn't like Alan Ameche is beyond me. He was the nicest fellow that ever lived. He was just a prince and I mean that seriously."

Marchetti's opinion of Ewbank is very similar.

"I once told Weeb that he was a great coach -- a great judge of talent and I think that was his strong point," Marchetti said. "He was a good planner, too, but he was weak leader.

"He couldn't hold the team together because he had a double standard for some players, and I admit I was one of his favorites. But some of us would make mistakes, and he wouldn't say nothing about it. He'd let it slide. Other guys, like Alan, he'd be all over them for every little thing.

"What happens when a coach is like that is you eventually lose the team. Everybody takes advantage of the situation, and that's what happened with Weeb."

Ewbank inherited a weak Colts team, which was 3–9 in their first year in Baltimore in 1953. The Colts were also 3–9 in 1954, Ewbank's first season in Baltimore, but they began a steady ascent to the top after that. The team was 5-6-1 in Ameche's rookie season of 1955; 5-7 in 1956, quarterback Johnny Unitas's first season with the team; and 7–5 in 1957. With Unitas fully settled in, the Colts won back-to-back world championships in 1958 and 1959.

But mediocrity set in, and the Colts went 21–19 in the following three seasons. Whether or not it was because Ewbank "lost the team," as Marchetti put it, Ewbank was replaced by another legendary coach, Don Shula, in 1963.

"When you lose control of the team, you can be the best organized coach in the world, but it doesn't do you any good," Marchetti said. "After four or five years in Baltimore, he lost control of the Colts. You can look at Weeb's history. He had a great three or four years in New York [with the Jets] too, but then he lost control of that team, too.

"Most of the players didn't like Don Shula, but he had their respect. If they broke a curfew, they knew it was going to cost them 500 bucks, no matter who they were. Weeb wouldn't bother to fine certain people on the team, and you can't have a double standard like that."

Ameche may have been tardy to meetings, but he didn't have to worry about being fined for breaking curfew. He was not one of the "party boys" clique that exists on every NFL team.

"Alan and I were friends from the start, but we really didn't hang out that much," Marchetti said. "Some of us liked to drink a lot of beer after games, but Alan went home to his family. He smoked for a little while, but he quit that, too, but I never really knew him to drink.

"When we'd go on the road, a lot of us would go out and have some laughs, even some of the married guys would go along, but Alan hung out with the guys who went to the movies, when Donovan and [Bill] Pellington and me would go to a tap room and have a few beers.

"Alan just wasn't that type at all."

Despite their differences in what they considered an entertaining night out, Marchetti and Ameche became fast friends, and Marchetti remembers what brought them together at their first mutual training camp at Western Maryland College.

"I knew Alan was a good guy from the get go and I'll tell you why," Marchetti said. "My brother [Angelo "Itsy" Marchetti] tried out for the Colts the same year Alan was a rookie, and he and Alan made friends right away.

"Here's my brother, who had no reputation or anything, and Alan is the Heisman Trophy winner, big star coming in, and he and Itsy are friends right away. You don't usually see a superstar coming in to camp and hanging out with a guy trying to make the team who didn't really have a chance.

"Angelo had a slim chance of making it, because he had been out of football for a couple years. He was the type of guy who never wanted to leave Antioch [California]; just be around his family and go fishing. That's all he had on his mind.

"So I like Alan and we hung out a little, but I wouldn't say I took him under my wing or anything like that. We would talk about things that might happen [on the football field] or whatever. But on a friendly basis.

"We didn't hang out too much because he was married and I was batching it back then. He didn't need anybody to take him under their wing. He was a tough guy and he could take it."

Marchetti remembers his first face-to-face encounter with Ameche after the disturbing incident with Ewbank.

"The first time I ever really met Alan was at the fourth floor of a dorm at Westminster. I went up to see my brother, and there was Alan, playing cards with five or six of the other rookies. Alan got along with everybody. They all spoke highly of him."

Ameche may have been popular with his teammates, but not all of the NFL's talent scouts were unanimous in their praise of the rookie fullback. Despite the sterling credentials that Ameche brought with him from Wis- consin, there were still doubts how his skills would translate in the NFL.

In a story that appeared in the Baltimore Sun on January 14, 1959, John Steadman wrote:

But those doubts about Ameche, as chronicled by Steadman, might offer some insight as to why Ewbank had been so quick to pounce on the rookie. With the third pick in the entire 1955 draft, the up-and-coming Colts couldn't afford a clunker.

"To be honest with you, I think that's what Weeb had in mind for Alan ... to play linebacker," Marchetti said. "You know Alan played linebacker in college.

"But it never got to that point because Alan did so well running the ball. He very seldom made a mistake. He did all the things a rookie should do."

Any plans Ewbank may have had for switching Ameche and his awkward-looking style to the defensive side of the ball were soon shelved. In his regular-season professional debut, Ameche ran 79 yards for a touchdown the first time he touched the ball in the game against the Chicago Bears in Baltimore.

Ameche rushed for 194 yards on that afternoon. Some consider it the greatest game ever by a Colts running back because he did it in just 15 carries -- an incredible 13 yards per carry.

-- Excerpted by permission from Alan Ameche: The Story Of The Horse by Dan Manoyan. Copyright (c) 2012 by Dan Manoyan. Published by Terrace Books, A Trade Imprint Of The University Of Wisconsin Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon and Barnes & Noble.