Hall of Fame coach Jim Boeheim is known for his fierce competitive drive and loyalty to Syracuse, and his efforts paid off with an NCAA championship in 2003 after years of having teams fall just short of the title. Color Him Orange: The Jim Boeheim Story examines the people who shaped him as an individual and a coach and the great players he has led, including Pearl Washington, whose decision to go to Syracuse was a pivotal moment in the program's leap to the nation's elite.

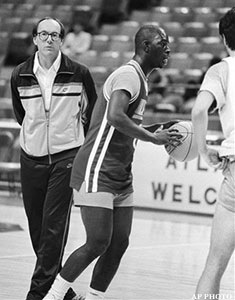

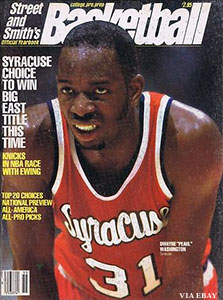

The most significant victory for Syracuse basketball during the '82–83 season would be scored away from the court. On February 20, 1983, during a halftime interview of a nationally televised game between St. John's and DePaul, Dwayne "Pearl" Washington told CBS commentator Al McGuire that he would be attending Syracuse. "I can't underscore how big a moment that was for our program," Boeheim said. "I believe at that point we officially went from being an Eastern program to a national program. Everybody knew who the Pearl was. I'd get off of a plane in L.A. and somebody would say, 'There's Pearl's coach.'" He was the guy who opened the door for us and enabled us to land recruits not just from the East Coast or the Midwest but from the entire country."

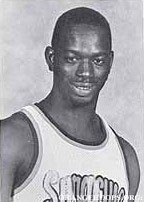

Boeheim was right about the Pied Piper impact Washington would have on SU's recruiting and the fact that his legend was already well established before he ever set foot on the hardwood court beneath the Dome. The chunky, 6'2" guard with the wicked cross-over dribble and the deceptive Globetrotter-like moves had been electrifying fans and demoralizing defenders for years on the asphalt, bent-rimmed playgrounds of New York City. His hoop dream began as a four-year- old in Brownsville -- a section of Brooklyn that one writer said "looks like bombed-out London during World War II." Even though his talent was evident right away, Washington didn't enjoy playing the game at first. "My older brother, Beaver, really is the only reason I kept at it," he said. "He told me he was going to beat me up if I didn't stay with it. He told me I had this gift, and he wasn't going to let me squander it. Looking back, I'm glad that he threatened me that way because he saw something in me that I was too young to notice, when it came to basketball."

By age 10, Washington was playing against and dribbling past the likes of NBA stars World B. Free and Sly Williams in pickup games. Beaver Washington said he recalls scrimmages on the courts at King Towers in Harlem where the crowds were so big that some people had to climb trees or head to the roofs of nearby tenements to catch a glimpse of the young basketball magician. His mounting legion of fans already were calling him "Pearl" because his nifty moves were reminiscent of Earl "The Pearl" Monroe, the former Big Apple basketball legend who had entertained many on these same courts before becoming an NBA star with the Baltimore Bullets and the New York Knicks. Somealso referred to Washington as "Black Magic" and "Pac Man," after a popular video game of the day in which you attempted to gobble up as many dots and ghosts as possible.

If there was a weakness in Pearl's game, it was his outside shooting. But his ability to penetrate against virtually any defense more than made up for those deficiencies. In an effort to force Washington to work on his jumper, Boys and Girls High School coach Paul Brown would occasionally put seven men on defense in practices. It didn't matter. Pearl still found a way to get to the basket. "Dwayne can't be stopped when he has it in his mind to score," Brown said, sighing. "He shoots layups against seven-man zones."

Pearl's legend would grow exponentially in high school. People raved about how, as a sophomore, he slashed his way to 16 first-quarter points in a game against a team of Boston scholastic all-stars that featured intimidating, shot-blocking center Patrick Ewing. It would be the first of several classic battles between him and ewing, who would play for Big East rival Georgetown. During his junior season at Boys and Girls High -- the same school that produced basketball heroes Connie Hawkins and Lenny Wilkens -- Pearl scored 39 points in an upset of Camden, New Jersey, at the time the top-ranked team in the nation. That same season, Washington had an 82-point game.

By his senior season in 1982–83, more than 300 colleges were recruiting him, perhaps none more fiercely than North Carolina State, which was coached by the flamboyant Jim Valvano. When Washington stepped off the plane in Raleigh, North Carolina, for his official visit, he was greeted by Wolfpack assistant coach Tom Abatemarco, who suddenly began tearing off his sport coat, tie, and shirt to reveal a red T-shirt reading, "Welcome Pearl." During his tour of the North Carolina State campus, Washington was treated to more theatrics. He was brought to the darkened basketball arena. The instant he walked through the doors, a light flickered on revealing a Wolfpack jersey bearing Washington's name and number draped over a chair at center court.

The New York tabloids only fueled the hype and hysteria. People throughout basketball chimed in with their accolades. Utica College coach Larry Costello, who had won an NBA championship as a player with Wilt Chamberlain and as a coach with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Oscar Robertson, called Washington "a miniature Oscar Robertson. He can do what he wants on the basketball court. You just can't guard him one-on-one. And he sees the entire court so well." High school super- scout Howie Garfinkel called him "the best high school guard from the east since Calvin Murphy." Al Menendez, a scout for the New Jersey Nets, said, "If Pearl would have played for us last year, we would have beaten the Washington Bullets in our playoff series." Syracuse assistant Brendan Malone, a New York City native, called him "the best guard I've ever seen coming out of the city. Pearl can penetrate a crowded, rush-hour train in Manhattan and come out of the car without picking up a foul." And Boeheim gushed about Pearl's charisma, saying: "He doesn't disappoint. People come in with expectations about him, and they always leave happy."

Despite all the headlines and air time devoted to him, Pearl remained remarkably grounded. "With all the publicity he's received," Brown said, "Dwayne still is what I call a down-to-earth kid."

The hype, though, did go to his head in a different way. The barrage of recruiting letters and phone calls became so overwhelming during the first part of his senior year of high school that he began developing migraine headaches. Originally, he had intended to wait until the end of the season to make a decision about which college he would attend. However, those plans changed.

"I wanted to get it over with because it was really starting to weigh on me," he said. "That's why I decided not to wait any longer." During his nationally televised interview with McGuire he explained his reasons for choosing Syracuse. "It is the right school for me for all the right reasons," he said. "They have a great communications department, and that is going to be my major in college. Someday I'd like to be a TV sportscaster. Syracuse also is in the Big East, which is my favorite conference. It has a great schedule, and it's close enough for my family to see most of my games."

Boeheim, who had been recruiting Washington for four years, couldn't have been more elated. He understood completely the ramifications. This clearly was a seminal moment in the history of the program and the university. "Dwayne is unusually strong and mature for his age, so he won't have any difficulty fitting right in at the college level," the coach said. "Also, his running style of play fits in perfectly with ours. He'll be a terrific addition to our team and will make all our players better."

Reflecting years later on his decision to go to SU, Washington cited Boeheim's low-key approach. "You experience a lot of phoniness and B.S. when you are recruited by as many programs as I was," he said. "The thing many coaches don't realize is that kids are usually smart enough to see through that stuff. Coach Boeheim kind of let the program and the school sell itself. He wasn't overbearing, throwing some huge sales pitch my way." Ever the entertainer, Pearl admitted the opportunity to play basketball in front of huge crowds inside the Dome also was a major appeal. "It was the largest stage I'd ever seen," he said. "What other school are you going to go to where you're going to play in front of 32,000 to 33,000 people? It really was amazing to come up there and see a place that big. I wanted to play on that stage." Pearl's decision resulted in 2,000 additional basketball season-ticket sales at SU and guaranteed a record six 30,000-plus crowds during his freshman season in the Dome. "Dwayne has gotten everyone excited," Boeheim said at the time. "If I were a fan, I'd pay to see him, too."

For every high school phenom who makes the transition to college superstardom, there are scores of others who fade into oblivion, never to be heard from again. However, Washington, who had been a man among boys in gyms and playgrounds throughout the Big Apple, was confident he'd be able to bridge the talent gap between scholastic hoops and the rugged Big East Conference. "People ask me if I'm feeling pressure because everybody is expecting so much from me this year, and I tell them 'No,'" Washington said on the eve of his college debut. "After all the recruiting and media coverage I've had since I was an eighth-grader, I know I can handle this."

Boeheim was confident he could, too. But in his comments to the media before Pearl's first practice, the SU coach attempted to lower some of the enormous expectations being placed on the freshman point guard's broad shoulders. Boeheim, a master psychologist, was sending a message not only to the fans and media but also to Pearl himself. "He had no competition in high school," the coach began. "He'll be pushed here in practice, which is something he needs. He was a great player on the high school level. Now, he's got to start all over again to prove to everybody how great he is here. He may be our best player and he may be our sixth best. Remember, last year's most-recruited freshman in the Big East was Villanova's Harold Pressley, and he averaged less than five points.

"Pearl must improve his shooting if he's going to realize his potential," Boeheim continued. "He also must cut down on his turnovers and not let himself get too lazy when the game isn't close. He's very strong and quick and he can go left or right equally well, and he has that little extra instinct to make the right play. Still, defense should be his strength, and we'll push him on that. He can be as good as Eddie Moss on disrupting with defense. We're looking forward for him to do that."

Everything he said was true. In reality, though, even the outwardly cautious Boeheim was having difficulty curbing his enthusiasm. He knew deep down he would be coaching the most charismatic and gifted player SU had seen since Dave Bing two decades earlier. And he couldn't wait to see the Pearl work his wizardry in orange.

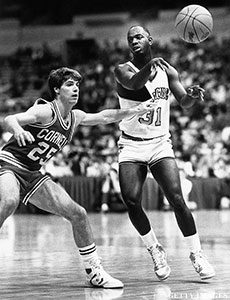

Although he had dazzled Dome denizens, teammates, and opponents while leading the 'Cuse to an 11–3 start his freshman season, Washington didn't truly become a bona fide Syracuse sports legend until game 15 against Boston College on January 21, 1984. It was on that night, beneath the Teflon big top, that the Pearl hit "the shot heard 'round the college basketball world."

Minutes after Washington's almost nonchalant, buzzer-beating halfcourt shot had given Syracuse a stunning 75–73 victory and touched off "fandemonium" in the Dome, his teammate, Sean Kerins, proclaimed: "The Pearl has arrived."

-- Excerpted by permission from Color Him Orange: The Jim Boeheim Story by Scott Pitoniak. Copyright (c) 2011 by Scott Pitoniak. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase at Triumph Books, Barnes & Noble and Amazon.