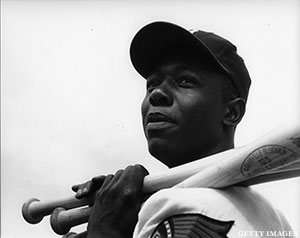

This story has mustard on it, but that makes it even better. Once, Henry Aaron struck out three times in one game. The pitcher in question used to nibble on a toothpick as comfortably as Aaron rolled his bat in the palms of his hands. This time the pick topped the hammer.

“That was the most embarrassing feeling in the world,” Aaron told David Letterman on the CBS Late Show last week. “I remember my third year, I faced Sam Jones and he struck me out three times in Chicago.”

Aaron held up three fingers for emphasis and said he met Jones for dinner that night: “I told him, ‘You’ll never have that opportunity against me again’ –- and I meant it. From that day on, he and I had an understanding.”

The understanding was that Aaron would never let Toothpick Sam Jones beat him like that again –- and he never did. That was no easy feat. One time, Jones stuck out nine Milwaukee Braves. He punched out everyone in the lineup except Aaron.

“Toothpick Sam” was so named because he rolled a toothpick between his teeth when he pitched –- a stylistic forerunner to Dusty Baker, one of Henry’s young teammates in Atlanta during the early 70s. Sportswriters looked at Sam’s droopy face and called him “Sad Sam” Jones, after a white pitcher in the 1920s. But black ballplayers never called him Sad Sam. He was always Toothpick –- toothpick thin, toothpick in the mouth, curveball that snapped like a twig.

Toothpick Sam was lean, lanky and loose, a smooth and explosive right-hander who led the National League in strikeouts three times. A clever scout might call his arm action “whippy,” might describe his tight curveball as a hard downer and his fastball as a two-seam demon with a tail. Twice, Jones whipped NL hitters for more than 200 strikeouts, including 225 with the 1958 Cardinals.

Jones was pitching for the Cubs in the game that Aaron recalled on Letterman. A careful study of box scores revealed it was April 20, 1955 at Wrigley Field.

Aaron thought it was his third year in the big leagues. It was actually his second. He said Jones struck him out three times, but Aaron was better than he remembered. Jones struck him out twice –- swinging in the first inning and looking in the second, which alone had to burn itself into Aaron’s memory because he almost never struck out twice in a row when he was young.

In between Aaron’s misery, the Braves ambushed Jones for 1 2/3 innings. Bobby Thomson hit a grand slam to chase him. Maybe the story is just better if Toothpick strikes out Aaron a third time.

But Aaron did strike out three times in that game, which also rarely happened, and probably still stings the inner gamer of a man who recently turned 77. Or, it’s a white lie to make a good story great and a tip of the hat to Toothpick, like Aaron, a former Negro Leaguer.

In the top of the sixth, Aaron faced a right-handed reliever named John Andre, who pitched only 22 major league games, all in 1955, and had 19 strikeouts. One of those was a strikeout Aaron never forgot, even if he changes the pitcher in the re-telling as a way of saluting Toothpick.

While Aaron showed some of his old fire while sitting on Letterman’s couch, there was also camaraderie in his words. When Aaron recounted that he and Jones had dinner after the game, it offered a reminder of how former Negro League ballplayers in the 1950s remained tightly knit in the majors –- all they had was each other. They had come up through the segregated minor leagues, segregated spring training and still faced travel segregation in some major league towns. They were the few and lucky ones who had seen life on both ends.

Aaron played a short hitch at shortstop with the Indianapolis Clowns before the Boston Braves signed him in 1952. Jones, shy and light skinned but fiercely proud of his heritage, followed the money through various clubs, most notably as ace of the Cleveland Buckeyes, where he got the attention of the hometown Indians and was signed in 1950.

The Hammer is a ham now –- the consummate storyteller. It’s hard to imagine that this was once a scared kid from Alabama who told interviewers that he didn’t care what anybody threw him, or such an aggressive ballplayer that in 1959 he slid so hard into Jones covering third base that he spiked him and jammed the toothpick into his throat.

Henry probably took Sam out to dinner that night, too, but that’s a story best kept between the Hammer and the Toothpick, who died in 1971 and never lived to see the home run trot Letterman asked about, and never again owned Henry the same way he did one afternoon in Wrigley Field.