One-on-one, locked up in man, defensive back drills, the two NFL progenies go at it every day during Heritage Hall (Okla.) football practice.

The respective sons of Barry Sanders and Derrick Shepard insist on covering each other and also race during 300-yard shuttle sprints.

"They're always step for step and they're battling," says Heritage Hall coach Andy Bogert. "That's what so great about them. They push each other hard every day."

Despite the intense competition between them, or maybe because of it, the two big men on campus -- 17-year-old Barry James Sanders and 18-year-old Sterling Shepard -- are buddies.

They hang out constantly. The defensive backs jokingly bicker about who should make the defensive calls. Shepard makes fun of Sanders' wardrobe. They play video games, attend Thunder games and recently went to a Maroon 5 concert.

"We're like always with each other," Shepard said. "We're definitely tight off the field."

They have more in common than talent.

At a private school with just 370 high school students, both of these senior football stars are sons of former NFL players. The elder Sanders was a Lions Hall of Fame running back, and Shepard's dad was a wide receiver for the Redskins, Saints and Cowboys.

"It is a crazy thing," Bogert says. "It's pretty amazing."

Because of his legendary father, Sanders has been under the spotlight since junior high. To avoid a potential problem, Bogert gathered his varsity players during Sanders' freshman season, emphasizing the attention was not Sanders' fault. He delivered a speech, which helped quell any possible jealousy from the other players.

"Guys, this is Barry Sanders' son," Bogert told the team. "No matter what happens, he's gonna get press. You guys have got to get used to that. It’s no insult to you."

Though still a bit behind Sanders in national publicity, the Oklahoma-bound Shepard has emerged as Sanders' equal on the field. The Oklahoman even ran a column debating which Heritage Hall star was the best player in the state.

That answer may be in the eye of the beholder, but who wins those daily DB drills?

"He's much quicker than I am," Sanders says. "He's a better receiver than I am (a) corner. So he gets me on most of the one-on-ones when I'm trying to guard him."

Laughing upon hearing Sanders' response, Shepard said: "I think he’s being generous."

They are both more generous than they realize.

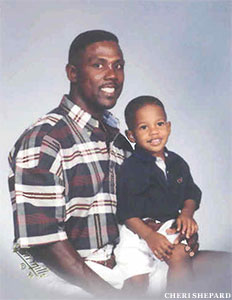

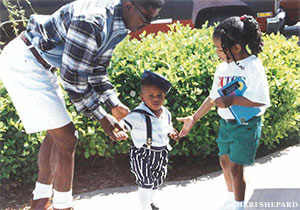

Shepard's life took a tragic turn at a young age.

Six-year-old Sterling and his two sisters were celebrating their cousin's 18th birthday at their grandmother’s house when Oklahoma assistant coach, Jackie Shipp, a close family friend, called.

He told the family Derrick Shepard had died.

"It's like your life just being turned upside down in seconds," says Cheri Shepard, Sterling's mother and Derrick's wife.

Derrick Shepard was just 35 when he suffered a heart attack. The University of Wyoming wide receivers coach, who had an enlarged heart, passed away after a game of racquetball.

Of the three siblings under 10, Sterling took the news the hardest. At the funeral, Cheri held him as he wailed like a "wounded animal."

At first Cheri said just getting her children to school was a challenge. But they would adopt Derrick's positive spirit.

"I could either go and hide and put the covers over my head and cry about it or just kind of stick it out," she says. "I would just tell the kids, 'Your dad didn't want us to be sad. He wants us just to enjoy life and be happy. So that's what we’re going to do.'"

Sterling honors his father every game day.

He wears No. 3, Derrick's jersey number when he starred for Oklahoma during 1984 and 1985. Sterling also writes "RIP" and "DSHEP" on his taped-up wrists before each game. After he scores a touchdown, he kneels down and points to the sky.

"I constantly think of him," Sterling says. "He's definitely in my thoughts as I'm playing."

Cheri said Derrick used to make his son, then just a toddler, watch football teams practice and study the players' form. Because of his father's coaching and football knowledge, Sterling believes he would be an even better player if his father were around to provide further instruction.

"I know nothing about football," Cheri says. "So he can't really get any feedback from me."

Barry Sanders does not guide his son in football either, even though he knows how to succeed at the game's highest level.

"The only thing he really talks to me about is being the best man I can be," says Barry J. Sanders, "and what it takes to be successful off the field."

The Detroit legend has focused on being a father instead of a coach to his son. He viewed Sanders hanging out with good peers and continuing to avoid negative influences as a far more important goal.

"I can't think of anything I've given him advice on as far as (playing) ball," Sanders says. "There's going to be a lot of advice he's going to need, and probably the thing that he'll need the least help with will be football ... The football part of it -- even though it's not easy -- is a heck of a lot easier than a lot of this other stuff that us parents have to guide our kids on."

Arriving at game time and sitting on the smaller, side bleachers, Sanders attends more than half of Heritage Hall's football games. Wearing a hat, he remains inconspicuous, and fans mostly leave him alone, which is what the notoriously reticent Hall of Famer prefers.

Sanders owns a car dealership in Oklahoma but resides in Bloomfield, Mich. with his wife, Lauren, and his three other sons. Barry J. Sanders lives with his mother, Aletha House, in the Oklahoma City area.

Cheri, a human resources manager at Chesapeake Energy, has become the integral figure in Sterling's life.

"My mom has been like a dad and a mom," Sterling says. "There's nothing more I could ask than to have a mom like that."

Shepard truly emerged from Sanders' shadow last season.

As a freshman he was just 5-7, 140 pounds. A concussion slowed his sophomore campaign.

But last year, Sanders suffered a season-ending foot injury in week six, and Shepard filled the void.

"He stepped up big time," Bogert says.

Bogert employed him in a versatile, Wildcat quarterback role. To prevent offenses from keying on Shepard, Bogert moved him around in a similar fashion to the way he used Patriots wideout Wes Welker at Heritage Hall. Bogert was the offensive coordinator during Welker’s playing days.

While playing myriad positions -- quarterback, wide receiver, running back -- Shepard lined up behind center, in the slot, in the backfield and in motion.

"He's a very versatile athlete," Bogert says. "He literally played every offensive position we had."

And the results were staggering. Shepard scored 34 touchdowns. He had 1,015 receiving yards and 571 rushing yards. On defense, Shepard added 103 tackles and eight interceptions.

During the 3A state title game, Kingfisher led Heritage Hall, 14-0, at halftime, and Bogert approached Shepard.

"Settle down," Bogert told his player. "We're going to put this game in your hands."

Shepard responded with four second-half touchdowns, and Heritage Hall won, 28-21.

The 5-11, 185-pounder has started 2011 in the same scintillating fashion, returning the opening kickoff for a 94-yard touchdown.

On offense this year, Bogert still uses him in Wildcat formations about five times a game, but Shepard mostly plays wide receiver.

"You throw it up to him, and it's almost a guaranteed catch," Sanders says. "Any time he gets the ball, he's a threat to score."

Shepard and Sanders complement each other. The 5-10, 185-pound Sanders spearheads the running game, while Shepard does the same for the passing game. Sanders has 346 total yards and nine touchdowns, and Shepard has 547 and seven.

On the defensive side, Sanders is the shutdown cornerback while Shepard roams at free safety. But if they face a pass-heavy offense, they both play corner.

At Oklahoma, Shepard likely will play slot receiver. He has a 40-inch vertical leap and 4.4, 40 speed. Scouts will be watching.

"If he stays healthy,” Bogert says, "I firmly believe he'll play on Sundays."

The defending 3A state champions are more than just Shepard and Sanders.

The Chargers, 5-0, have 18 seniors, and six players likely will go on to play Division-I football, including 6-3, 240 lb. tight end/defensive tackle Quintaz Struble and 6-1, 280 offensive/defensive lineman Markus Wakefield.

"It's the most talent we've had," Bogert says.

After this season Shepard and Sanders will go their separate ways.

Shepard will attend Oklahoma, where he has deep ties. His father and two uncles, Woodie and Darrell Shepard, also played there. Derrick was a graduate assistant at Oklahoma before he joined Mark Stoops on the Wyoming staff, and Oklahoma head coach Bob Stoops helped Shepard land that Wyoming job.

"He was a big part of my life," Sterling says of his dad, "and I wish he had stuck around to see what I'm doing now."

Sanders says he will announce his decision at the U.S. Army All-American Bowl and is considering UCLA, Stanford, Florida State, Alabama and Oklahoma State.

As a result of the latter option, the trash talk between Sanders and Shepard escalates before the latest chapter of the OU-OSU Bedlam Series.

"They give each other crap all the time," Bogert says.

But they also give each other support -- not the kind that replaces an every day father figure, but definitely the kind that continues what a father started.

Shepard will attend his dad's school. Sanders has not yet decided if he will follow in his father's footsteps at OSU.

But whether Sanders is on his rival's sideline or a different field altogether next season, Shepard will miss him.

"That's my boy," Shepard says. "Not being with him every day is going to be kind of tough."

Tune in to RivalsHighTV this weekend and all season long!

Related Stories:

-- Hockey Pop: Popeye Jones' Son Is A Rising Star, But Not In Basketball

-- MLB Draft: The 2011 All-Bloodlines Team Includes A Gretzky, A Garvey And An I-Rod

-- Jason Terry Of The Mavericks Finds Time To Coach Daughter's Sixth-Grade AAU Team