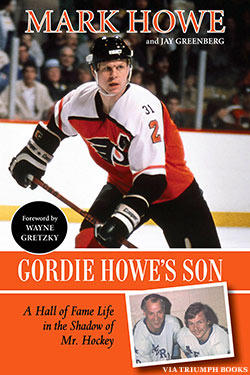

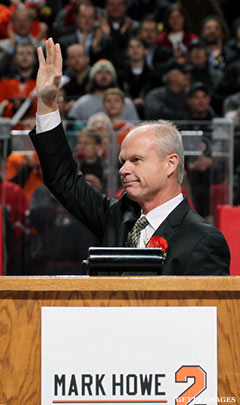

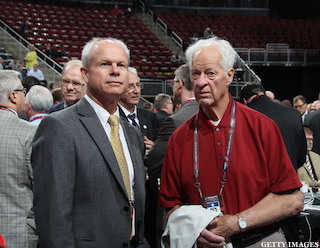

Mark Howe emerged from the shadow cast by his iconic father Gordie to achieve greatness. A U.S. Olympic silver medalist at age 16, and a member of the Memorial Cup champion Toronto Marlboros, Howe went on to play seven seasons alongside his father, Gordie, and brother, Marty, for the WHA's two-time champion Houston Aeros and New England and Hartford Whalers before becoming a four-time NHL All-Star with the Philadelphia Flyers. Howe, elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2011, recounts the joys and travails endured by the sport's most beloved family in Gordie Howe's Son: A Hall of Fame Life in the Shadow of Mr. Hockey.

I first realized I had a famous father when he would take me places and everybody wanted his autograph. But I just thought that was normal. For as long as I remember, Gordie Howe has been my dad more than Mr. Hockey.

Interviewers have asked, "What's it like being Gordie Howe's son?" I've always assumed it was no different than being anybody’s son who grew up in a loving, supportive family.

Of course, I felt differently the night he scored his 545th goal to pass Maurice Richard for the all-time lead in the NHL. I was eight years old and the cheering at Detroit’s Olympia that night -- November 10, 1963 -- seemed to last forever. I remember thinking, "Wow, I’m the only person in here who can say, 'That's my dad!'"

A wealth of pride, however, was the only wealth into which I was born. In the '50s and '60s, not even being the planet’s best hockey player translated into big dollars. When I came into the world on May 28, 1955 -- 15 months after my brother Marty -- Gordie Howe, the star of the Stanley Cup champion Red Wings, earned a salary of $10,000. That's worth $86,000 today, when the minimum NHL salary is $525,000.

Making the middle class was a huge step up for Dad, though. As the sixth of nine kids -- another two were stillborn -- of Katherine and Ab Howe, my father was raised in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in a house with no running water, necessitating that he shower at school. Thank God he liked oatmeal, which he sometimes had to eat three times a day. But the house in which his family lived so embarrassed him that until he made enough money to buy his parents a new place in Saskatoon, my father would not invite teammates to come visit over the summer.

Dad grew up delivering groceries in 30-below-zero weather and hunting the gophers that drove the Prairie farmers crazy, which would bring in a dollar a tail. I'm told that because of his struggles in school, he was a really shy and under-confident guy away from the rink. But that was only part of the reason he eyed my mother, Colleen, for weeks at his hangout, the Lucky Strike Bowling Lanes near the Olympia, before finally approaching her. Dad didn’t feel he had enough money for a proper date.

According to Mom, Dad was worried about making the mortgage payments when our growing family -- Marty was five, I was four, sister Cathy an infant, and baby Murray on the way a year later -- moved from the little ranch house on Stawell Avenue in northwest Detroit to the bigger, split-level home at 28780 Sunset Boulevard in Lathrup Village.

It seems amazing that the first time my grandparents ever saw their son play an NHL game was on Gordie Howe Night at the Olympia -- in his 13th season. But you have to realize that there wasn't money to pay for their transportation to Detroit. Until we had the means to buy a second car, my mother would bundle Marty and me for trips to the train station as late as 4 a.m. in order to pick up Dad from road trips.

When he wasn't traveling, my father did what had been expected of him since he was a kid: helping cook and clean. Even after he could afford to do so, Dad wouldn't pay people to do work on the house that he could perform himself. So Marty and I were given chores to earn our $5-a-week allowances. Even before I was old enough to be put in charge of cutting the lawn and removing snow, my once-a-week responsibility was to take everything out of our garage, clean it, and then put everything back.

I had a pretty good understanding of an honest day's work for a day's pay, a concept that was helped along in fifth grade when I was reminded there was a cost for bad decisions. One day after school, some friends and I had stopped at a little neighborhood drug store and didn’t have any money on us, so we stole candy and cakes. I took some Twinkies.

About an hour and half later, my hockey game in the driveway was in full swing when a police car pulled up. I had eaten my evidence, but one of the other kids had gotten caught when he got home. He told on all of us, so they were rounding up the other suspects. I tried to deny it, but in front of all my friends the police dragged me, totally embarrassed, into the house.

I took a belt whipping that day, but not from Dad. I remember him physically reprimanding me only once. I don’t recall what I did, but it must have been pretty bad because he slapped me in the ass with such force it felt like he broke my back. On this day, it was Mom who hit me so hard with the belt that blood was seeping from my lashes. I refused to give in and cry. Actually, Mom did an hour later, when she came to me shedding tears because she had hit me. But I certainly learned that day not to steal.

In our house, there were reprimands when we deserved them, but never any threats. Always, there was an awareness of our responsibilities, intensified by being Gordie Howe's kids.

Dad had struggled in school because he suffered from mild and undiagnosed dyslexia. When Detroit signed him at age 16 out of a training camp in Windsor, Ontario -- for a first-year pay of $2,300 and the promise of a Red Wings jacket -- and sent him to their farm team in Galt, Ontario, he dutifully showed up for the first day of high school. But, suddenly realizing he knew no one, my father gave his books away, walked to a metal plant, and took a job instead.

In his year at that factory, Dad actually worked his way into a low-level supervisory position. But he always regretted dropping out of school and felt that somebody from the hockey club should have stopped him. I think that’s why he took up crossword puzzles— a big-time passion of his—to improve his vocabulary. We did them together, and still do to this day.

So it wasn't just Mom who valued education in the Howe household. Homework had to be done before I could get to my game, either at a rink or in my driveway. I would always race home from school to get it out of the way. Fortunately, school came pretty easily to me, because it was a means to an end. The greatest thing my father passed on to me besides a sense of responsibility was a love of the game like his own.

"Is your father at work?” asked someone on the phone that I answered at age five.

"My dad doesn’t work, he plays hockey,” my mother remembers me saying.

For me, too, the game was no chore. Dad also gifted me his ability to skate. Mom and Dad always said that while the other kids’ ankles would bow in, mine would bow out for some reason -- probably genetic. I'm told I learned at age two by leaning on a folding chair that I would push around the ice, giving me something to help pull myself up when I fell.

By age four, I was playing on my first team: Teamsters 299, sponsored by the union. I remember a little about the outdoor rink -- Butzel Arena -- just up the street from our house in Lathrup Village. There were a couple of little bleachers and one tiny room where we could put our skates on. But you had to shovel the ice after it snowed.

Believe it or not, when I was really young, the Olympia was the only indoor rink in Detroit. My parents got together with some people and obtained the use of a closed factory in which they put up boards so that when it snowed you could still play, even if it was on natural ice in an unheated building. The train tracks that ran into the building were inactive, but as a five-year-old, I still worried about a train coming.

Mom and Dad created a rink in our front yard, too, setting their alarm clocks to come out at all hours of the night to move the hose they had attached to a ladder so they could flood the next section. After a couple of years without much sleep, my parents tried something easier by letting me skate on the ice on the cover atop our Lathrup Village backyard pool. But because I cut the winter pool cover with my skates and they worried about me falling through, that lasted only one year.

Later, they put up wooden planks and plastic, which eliminated the need to move the hose. The lights I hung around the arena for play after dark were also used for our Christmas decorations, and one year we won an originality award from the town of Lathrup Village.

Finally, a neighbor who owned a construction company came to our aid when he plowed a 200-by-85-foot rink—piled-up dirt served as the boards—in a vacant lot across the street. The town would open up a fire hydrant to flood the surface. That beat our little home rink in the front yard for reasons that included the location of the latter in front of a picture window, which I had broken one night when the puck bounced off the goal post. Dad was away and it was cold. Mom was not a happy camper.

By my count, I broke 12 windows in the house over the years. When I was playing in the driveway, I usually had a net, but, always going for the corners, I would sometimes miss, so it was bang, bang, bang against the aluminum garage door. After hours of that one day, Mom finally came out and said, “Put the door up.” So I did, and I think the very first ball I shot went through the garage, breaking the glass door leading into the kitchen and continuing down the hallway into the living room. In one straight shot, the ball ended up under the sofa at the far end of the house, leaving glass all over the kitchen.

Mom then asked me to put the door back down. She never told me to stop shooting, though. And we received encouragement from our parents about all of our passions, not just hockey.

When my sister, Cathy, hit her preteen years and began to object to being dragged to her brothers’ games, she ran track and became an excellent water skier. I don’t think any of us thought Murray, the best student in the family, was going anywhere in hockey; we believed he played because he thought it was expected of a Howe. Murray, now a doctor, insists he didn’t feel that pressure and that he really loved the game. I know he did, but there was little question he admired my dad so much that he wanted to follow in his footsteps.

Whatever pressure we felt came only from within. When Dad would attend our games, he would just watch, never yell or second-guess the coaching or do any of the things other parents would do. There wasn’t a lot of unsolicited advice from him or from my mom. Basically, you learned how to do everything on your own, and when you had questions, they always were there with the answers. And I believe the sense of family that guided almost everything we did came not only from the big one in which Dad grew up, but from the one my mother never really had.

Her parents, Margaret Sidney and Howard Mulvaney -- a trombonist who played with Benny Goodman, among other big bands— married and divorced young. Basically, Mom was raised by her great-aunt Elsie and great-uncle Hughie, who became the only people we knew well on that side of the family. The odd time at Christmas, we would go to Mom’s mother's place in Detroit, but the relationship was not great. Mom said her stepfather from her mother’s second marriage, Budd Joffa, was very good to her, but after Margaret’s second divorce, my mom lost track of him.

Howard, her biological father, was good at woodworking. So Mom, trying to spend more time with him and also help him out a bit financially, hired him once to do some restoration work for us and make some furniture. She also gave him a truck for the work he had done, but he totaled it while driving drunk a few weeks later. His drinking problem was so evident that Mom didn’t want him around her children, which put a huge strain on their relationship. He more or less drank himself out of our lives.

Mom always tried to patch things up with her parents, make them at least okay, but deep down, they weren’t. It’s my belief she did so much work with children’s charities because she drew a short straw when it came to her own parents.

Of course, she also couldn’t do enough for her husband and children, which Dad never took for granted. One time while we were eating dinner, he and Mom were in a squabble about something. After a while, he said, “I need to cool off for a minute,” so he got in the car and I hopped in with him. He had just started it up when I said, “I can’t believe what Mom’s saying. She is so mean.”

He snapped at me, “Don’t ever talk about your mother that way." I said, “I’m on your side!” And he repeated, "Don't ever talk about your mother that way."

They had a lot of patience for each other. Because she didn't like how people with the hockey club took advantage of his time for appearances and things, she wished he would stand up more for himself. But I don't think he ever thought she was nagging him about it; actually, he probably agreed with her. Still, because Dad wasn’t one to bark back, Mom would wind up with the bad rap because the Gordie Howe everyone loved couldn't do enough for people.

Because Dad was on the road or at practice or needing his nap on game days, Mom took charge of our hockey educations. She had some disagreements with the way minor programs were run by what was then the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States, so she formed some independent teams for us. Mom selected coaches not just to teach her own boys, but everybody’s on the club. After she had done her due diligence, I think she let the coaches, none of whom were screamers, do their thing. Jim Chapman, whom I had up to age 10, and who unfortunately later died in a car accident, was a very patient teaching coach.

Of course, the most essential hockey lesson Marty and I had to learn was how to cope with being the sons of the greatest player on earth. Even from a ridiculously early age, I would hear fans yelling, "You're not as good as your father,” to which Marty sometimes would yell back, "Who is?” Pretty good answer. But as our teams, in search of better competition, would go to Canada to play games, there would be a lot more—and tougher -- trash talk.

When our club became the first from the United States to enter the annual pee wee tournament in Quebec City, there were around 14,000 people at Le Colisée. All eyes were upon Gordie Howe’s eight- and nine-year-old sons, me on left wing, Marty on defense. Pretty intimidating. If, as we grew older, Marty ever fought any jealousy about me, the little brother becoming the better player in people’s eyes, I don’t think we ever discussed it. We spent most of our time talking about dealing with being Gordie Howe’s kids. And the best advice on that came from our mom.

"You have to learn to let it go in one ear and out the other," she said. “It is what it is, learn to accept it. Maybe there’s a negative side with all the attention you get. But let me make a list of all the positive things, like being able to go down to the Olympia and skate for six to eight hours. You can say, 'I'm Gordie Howe's son,’ and go anyplace in that building you want."

Every Red Wing would get two tickets per game. Later in Dad's career, when Mom was too busy with running his business stuff to go to every game, I would go out onto Grand River Avenue, sell the tickets at the face value of $7.50 each, then walk past a friendly ticket taker and go sit in the press box.

That wasn't the only example of my entrepreneurship. One Christmas, I surprised my parents with a request for a $450 top-of-the-line snowblower -- I had done my research -- with which to expand operations throughout the neighborhood. They loaned me the money. I had 25 contracts for three to five dollars per driveway and paid them back completely by Christmas the following year.

Fortunately, I never had to pay for a seat at our kitchen table with Bobby Baun, Bill Gadsby or other Red Wings after games, another perk of being Gordie's kid. Mom would let me stay up -- I even got the meal ready for them and drew the beers from the tap we had in the basement—and I would ask Frank Mahovlich about his aim on the goal he had scored that night, or question Bobby Baun about whether the shot he blocked had hurt him. Mostly, though, I just listened. My mother later said that at age nine, I already was preparing myself to be a professional.

A couple of times a year, when Dad was supposed to be dropping Marty and me off at elementary school on the way to practice, I would plead to go to the rink with him, and every once in a while, he would say okay. Mom was fine with that because I was a conscientious student and she knew time with Dad was precious to us. When he was home during the day after practice, we would be at school. During the playoffs, the team would be in Toledo for up to four or five weeks because Jack Adams, the general manager, wanted the players away from "distractions" like wives and kids. So when the Red Wings would be coming home late from a trip, I would ask Mom if I could wake up to see Dad for a little bit. She would say okay and I would get to spend 10 minutes with him before he would put me back to bed and get to sleep himself.

As long as my homework was done, I could go to the Red Wings games, even on school nights, which gave me the chance to see Dad some more. If the Wings were winning, I would leave my seat with about five minutes to go in the game and stand along the barricade -- the players had to go through the Olympia concourse to get to the locker room -- waiting for Dad to grab me and take me into the locker room.

Norm Ullman, Number 7 for Detroit, would always sit on one side of the bench. Dad, Number 9, was in the middle and Alex Delvecchio (Number 10) on the other side. I would sit with them while the coach would rant and rave. Dad remembered that once, when I was really young, I asked, "Who's that little fat guy?” meaning Jack Adams, and the next game, the policy was: no more kids in the locker room. I don’t know how long that rule lasted, but while Sid Abel, and then Gadsby, coached, it certainly no longer was enforced.

All the players were great to me. I can't remember one who wasn't, although I was embarrassed pretty badly by Toronto's Eddie Shack one time when I was serving as water boy/stick boy/tape boy in the visiting locker room.

There used to be a 45-rpm record called “Gordie Howe is the Greatest of Them All” that would be played in Detroit at playoff time. Eddie was on the training table in the middle of the visitors’ locker room, getting taped, and just as he saw I was going to ask him for his autograph, he started singing that song. I got so embarrassed I had to hide in the stick room.

Everybody made fun of Eddie, who was unable to write because of his dyslexia. So he got a stamp made with his alleged signature. When the crowds would form around him outside the locker room, he would pull out his pad and stamp away. I thought that was just the neatest thing.

Over to the left in the Red Wings' locker room was the stick rack. As I got older, I would grab a stick that Nick Libett or Dean Prentice would saw down to my size, and then the trainer, Lefty Wilson, would come out of the back, screaming at me (in mock anger) for stealing sticks. Everybody in the locker room would chuckle.

I wanted those sticks to play ball hockey on the stairs to the back balcony, where a railing and a wall created a sort-of goal. Even dressed up in my suit and tie -- that's what you wore to the games in those days—I would go off to the balcony, hopefully with another player's kid -- sometimes Jerry Sawchuk or Kenny Delvecchio—who could be the goaltender.

After Dad showered, he would sign every autograph, which I loved because that meant another 20 or 30 minutes to play on the stairs. But that also was him again teaching me by example, showing how he took care of the public and what a humble man he was. Dad graciously accepted the many things offered his way, but didn’t behave as though he had grown to expect them.

I saw him lose patience in public only three or four times. When, instead of asking nicely, somebody would demand an autograph with a “Sign here!” Dad would usually sign the word "Here." That's his sense of humor. Once, at an Italian restaurant near the Olympia, Dad had food halfway to his mouth when some guy shoved a piece of paper right against the fork and said, “Sign this!" Dad had a few things to say that were not nice, but fitting for what the guy had done.

Another time, Marty and I were playing in a junior game in Chatham, Ontario, against a team with which we had a pretty good rivalry. Throughout the game, people were all over Marty and me with "Your old man sucks,” and all over Dad with “You're over the hill -- you ought to retire, you bum."

Afterward, people asked, "Hey Gordie, can I have your autograph?” But after two and a half hours of verbal abuse, they had no chance of getting it. He didn’t say anything other than, “I’m not signing tonight.”

Then there was the time just my father and I were in the car when some kid cut him off on Southfield Road, near home. Dad drove around in front of the guy, but the kid got back in front again and slammed on his brakes for spite.

When the cars came up to a light, Dad put ours in park and started out. The guy looked back and took off through the light. When Dad got back into the car, all he said was, "Don't tell your mother."

I read about one other time where some guy spit on a Red Wing right in front of Dad as the team got on the bus after a game. Apparently, Dad left the creep crumpled against the back wheel of the vehicle. The guy sued and the team had to make a settlement.

It took something really abusive to provoke Dad. His thoughtfulness could be incredible. When he was finished cleaning his own windshield at the gas station, my father would do somebody else's. Every once in a while, he would shovel the neighbors’ driveways, rake their leaves or mow their lawns without being asked.

One time when there was a snowstorm and my team couldn’t get back from a game in southern Ontario, he was out with the snowblower in the wee hours, taking care of my obligations in the neighborhood. And as he has gotten older, my father continues to do even more of those kind things for people.

Always, there has been this incredible grace to him. Every once in a while, when he had to go to Toronto, I would ride with him. Dad was a notoriously fast driver; we were headed up the 401 doing something like 95–100 miles per hour when he got pulled over near Chatham.

Dad kept autographed pictures in the glove box of the car. In getting out his registration, he would intentionally put the pictures on the floor within the cop’s line of vision.

When this patrolman said, "Oh Gordie, it’s you,” Dad gave him the line, “Yeah, how you doing? Got any kids?”

The cop said, "Yeah, I got three." And Dad said, “Would you like an autograph for them?"

The patrolman said, “No thanks, Gordie, we already got three sets of those." Seems the same guy had been stopping Dad for years. I remember the cop saying, "Look, Gordie, we're concerned for your life. If you get a flat tire going this fast, anything can happen. We just want you to slow down.” Sure, he was letting Dad go because he was Gordie Howe, but not entirely. Dad just has a way with people.

One day, he playfully scooped up some ice shavings and threw them over the glass on some quadriplegic kids who were watching practice. One of them was laughing as the snow ran down his face, but when the next Red Wing did it, too, that kid was pissed off. He loved it only when Gordie Howe did it.

That's Dad’s natural gift, a mystique or whatever you want to call it, the best part of what he is. His interaction with people is phenomenal and is what keeps him ticking today.

In 1965, when I was 10, Dad signed a $10,000 yearly deal with Eaton's department store to travel coast to coast in Canada, visiting every store in the chain during July. Usually, when he got about halfway across the country, like to Winnipeg, I would fly out and travel with him for the final two weeks.

What I remember most about those trips were these picture cards he would pass out every day. Each night at 8 or 9 p.m., when we got back to the hotel, Dad would pre-sign 2,000 to 2,500 cards so he could spend more time the next day writing in things like “To John, best wishes” and thus have a little more time for each person.

If it was a town with only one Eaton's, you would spend a couple of hours at the store, and then they would take us golfing or fishing. Marty, who wasn't a golfer but liked the fishing part of it, went a couple of times. Mostly, it was Dad and me. And every second with him was a treasure.

-- Excerpted by permission from Gordie Howe's Son: A Hall of Fame Life in the Shadow of Mr. Hockey by Mark Howe with Jay Greenberg. Copyright (c) 2013 by Mark Howe and Jay Greenberg. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.