In the 1980s, Ray Mancini was a national hero; the real-life Rocky who rose from the gritty streets of Youngstown, Ohio, to become boxing's All-American Boy. Growing up in the shadow of his father -- whose own boxing career was tragically cut short by injuries sustained in WWII -- Ray vowed to win the world championship title and national glory that Lenny, the original Boom Boom, had missed out on. But another tragedy awaited the younger Mancini -- this time in the ring itself. A story of loss and redemption and the bonds between fathers and sons, The Good Son: The Life of Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini by Mark Kriegel takes readers from the sweaty fight gyms of 1940s Brooklyn to the glamorous, if corrupt, televised fights of the 1980s, tracing the arcs of the very different careers of the Mancini men while depicting their personal relationships with the ring. Here is an excerpt. (Warning: This post contains adult language.)

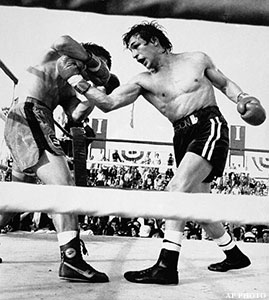

The longer it went, this stubborn accrual of brutalities, the more it thrilled -- not just the millions watching at home -- but his fellow celebrities at ringside. One could see Sinatra transfixed, his admiration palpable. Bill Cosby left his seat to volunteer advice in the champion's corner.

This was America's champion: symbolically potent, demographically perfect. And during this brief moment in American life the public observed little distinction between flesh and fable, between Boom Boom Mancini and Rocky Balboa.

Hey, people would ask, when you gonna kick that Mr. T's ass?

But against almost every expectation, this fight was even better than a movie. Each passing round became an homage to the champion's father, who had been a fighter himself. I never took a step back, he told his son.

The challenger, for his part, had no father to speak of, a source of great embarrassment back in his native Korea. But his manner of combat, the eagerness with which he endured abuse, seemed to gentle the condition of his birth, as if he'd descended from the Hwarang knights who famously admonished against retreat.

He was enchanted, said an old friend.

By now, both fighters were purplish and quilted with bruises.

And as the champion went wearily to his corner, he wondered what the fuck Bill Cosby was doing there and why he was speaking in that Fat Albert voice. Was this a dream?

What's he got to do? wondered the champion's corner man. Kill this kid?

One of the television announcers had seen it before. And between rounds, he issued a muttering prophesy: Something bad's going to happen ...

Almost three decades later, Ray Mancini mumbles a prayer as a waiter sets the plate before him. Red sauce, pink sauce, white sauce, or grilled. It matters not. Mancini's devotional rituals do not change.

The regulars at table twenty-four enjoy the whole bit, from mannerism to mantra, the way it ends with Ray pressing fingers to his lips. But, more than that, they envy his capacity to believe.

Fucking Ray'll believe anything, they say.

Present, as usual, are the hard-wired playwright, the muchloved television star, and the producer who made it big with cop shows. Il Forno Trattoria -- "the joint," as they call it -- is tucked into a strip mall on Ocean Park Boulevard in Santa Monica. "We all grew up in neighborhoods where a great premium was placed on being able to sit around and talk shit," explains the playwright.

"So, instead of this Hollywood nonsense, guys talking about their diets, we remember."

Remember the fight? Remember the night?

And that fat detective from Brooklyn, remember him?

Louie Eppolito, an ex-cop with an epic comb-over, had proclaimed himself a screenwriter. Everybody at table twenty-four tried to warn Ray. The guy was no good, dirty, mobbed up. Mancini listened to all the advice, of course, then promptly bankrolled Eppolito's screenplay.

The resulting motion picture went straight to video while Eppolito got life plus one hundred years for moonlighting as a mafia hit man. Still, the most corrupt detective in the history of the NYPD had failed to corrupt Mancini, or diminish the ingenuous instinct that made Ray a national hero. Ray liked Louie.

What's more, the guy had great stories.

"Ray loves the stories," says his ex-wife. "Don't you get it?"

He'll tell you his story is that of his father's. But, in fact, it's what he made of his father's story, an unwittingly theological construct he conceived as a child, while pondering sepia-toned glossies and brittle-brown clippings of a heroically battered boxer.

"I didn't win 'em all," said the father. "But I never took a step back."

Lenny Mancini had been the number-one contender in an abundantly talented lightweight division. However, his chance for a championship ended not with a title shot, but with fragments from an exploding mortar shell, keepsakes from the Wehrmacht he'd carry with him the rest of his life. That was November 10, 1944, just outside the French town of Metz. The Virgin Mary had appeared to him just days before, hovering over his trench.

A generation would pass before Lenny's youngest son would enter the national consciousness. Ray called himself "Boom Boom," too, just like the old man. But coming out of Youngstown, Ohio, in the early 1980s, he also represented those felled when the steel belt turned to rust. As refracted through the lens of television, Ray became The Last White Ethnic, even more valiant than violent, a redemptive fable produced by CBS Sports.

This teleplay, of course, made no mention of the older Mancini brother. With Ray on the cusp of fame, he was found with a .38-caliber slug an inch and a half behind the right ear. Nielsen families didn't want to hear that. "Boom Boom" was a family show, serialized for Saturday afternoons.

Ray won the lightweight title with a first round KO live from Vegas, the broadcast sponsored by Michelin ("the company that pioneered the radial"), Michelob ("smooth and mellow"), and the Norelco Rotatract rechargeable. That was 1982. He was only twenty-one, but already a modern allegory, as bankable as he was adored.

Warren Zevon wrote a song:

True story: Sinatra once sent Jilly Rizzo to Mancini's training camp to apologize.

"For what?" asked Ray.

"For not being here in person."

Yes, Sinatra was ringside when Mancini killed a man. If that's not exactly what happened, that's how it's remembered.

Duk Koo Kim hit the Korean exacta at birth: dirt poor and dark skinned. When Duk Koo was two, his father died. But the epic battle with Ray ennobled him. He'd become fierce for his fiancée, her belly already swollen with a son.

If only Kim had taken a step back, he might've lived to see that boy.

"Don't worry, Raymond," said his father. "It could've been you."

Could've been me?

It was like telling Ray to believe in ghosts.

Now Ray sits at table twenty-four, overlooking the strip mall's concrete veranda. It's likely he'll be joined by one of the regulars: the playwright David Mamet, the actor Ed O'Neill, or maybe Ray-Ray, now fifteen, the youngest of Mancini's three children.

He drives Ray-Ray to all his games -- freshman football and AAU basketball -- and makes sure the boy finishes his homework. Meanwhile, occasional patrons pull the waiter aside, asking for help in reconciling this dutiful dad with someone they think they remember.

"What was he in?" they ask.

"That's Ray 'Boom Boom' Mancini," says the waiter. "Lightweight champion of the world."

"He's the guy who killed the guy, right? The Korean?"

Soon, they'll make their way over to table twenty-four.

"I was a huge fan, champ."

"I remember Arguello."

"I remember Chacon."

"I remember your father. Huge fan."

Still, the most devout and deferential pilgrims belong to a phylum of the story-telling classes.

"The actors," says the waiter. "The guys who do make-believe, love the guys who do it for real."

"One loves being around fighters," says Mamet. "Everything in acting is subjective ... But you knock a guy out, that's something different."

Something better: John Garfield as Charley Davis, Sylvester Stallone as Rocky Balboa, Robert De Niro as Jake LaMotta. There's no better role. But if actors want to play fighters, then fighters want to play fighters, too. They know Hollywood doesn't love them as much as the idea of them.

Isn't that the point, though? To fuck with the stories until that line between player and pugilist becomes hopelessly blurred?

No surprise that Stallone produced Ray's story as a movie of the week.

Or that Mickey Rourke asked him to work his corner.

By then, of course, Ray wanted to be John Garfield. Mickey had to settle for casting old man Lenny as -- what else? -- a mumbly cornerman.

That was the eighties. LaMotta would bump into Ray at banquet-style press lunches. "You see Vickie?" he'd ask. "I'm talking to you, Ray. You fucking my wife?"

It only sounded like lines from the script. He meant it.

Then again, maybe Jake didn't know the difference. It's better to play a fighter than to be one. An actor doesn't lose his stories. The concussed mind of a fighter, however, becomes a spooky place. Dementia is a supernatural disease; the stories become ghosts.

"How do you keep a jackass in suspense?" asks Bobby Chacon.

Beat.

"I'll tell you tomorrow," he says, slapping his knee.

Chacon loves his jokes, reciting each one as if it had a virgin punch line. But he's even more delighted to sing:

His eyes grow large and giddy, like a small child or an old drunk, happily reassured by a familiar melody. But his voice isn't a voice so much as a long, low moan. It takes a practiced ear to understand Bobby "Schoolboy" Chacon, as he speaks in the language of ghosts.

"Tell Boom Boom it was the girls," he says. "That's the only reason he beat me."

Chacon trained for Mancini in a trailer park near Reno. At least that's how he recalls it these days: the girls materializing at the foot of each trailer and hiking up their skirts.

Hi, Bobby ...

"What could I do?" he asks.

What about me, Bobby?

"What was I supposed to do?"

I love you, Bobby.

"Tell Ray it was the girls."

Beat.

"How do you keep a jackass in suspense?"

Now, at table twenty-four, Ray inquires as to the condition of his erstwhile idol.

"He said the only reason you beat him was the girls."

"If I knew that, I would've sent more."

"How do you keep a jackass in suspense?"

"What?"

"He forgets. Keeps telling the same joke."

"Sure. Just like my father."

-- Excerpted by permission from The Good Son: The Life of Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini by Mark Kriegel. Copyright (c) 2012 by Mark Kriegel. Published by Free Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Mark on Twitter @MarkKriegel.