The 22-year-old major league catcher sat alone on a Saturday night in a restaurant inside Milwaukee's Knickerbocker Hotel, doing his best to digest an 0-for-4 day at the ballpark.

The waiter approached his table with wine -- whether it was a glass or bottle Joe Torre can't remember 50 years later -- set it down and passed along the message that accompanied the gift.

"Compliments of Sandy Koufax," the waiter said.

Torre, who was just beginning his career with the Milwaukee Braves, looked into the hotel's other restaurant and spotted the Dodgers' ace, who had struck him out three times earlier in the day.

He passed on a message for the waiter to return.

"You tell him I came to him all day," said Torre, who popped up the first pitch of his fourth plate appearance following the three strikeouts. "He can come to me tonight."

Within a few minutes, Koufax walked over, sat down and the two Brooklyn natives who had never met started talking baseball.

Torre soaked in every word, convinced to this day that he got much more out of the conversation than Koufax ever could have.

"I felt like I was a kid all over again," Torre says in a phone interview with ThePostGame.com.

That night, minutes turned into hours and the two continued to talk, one player to another, one baseball tale stacked on top of the one before it. That night, Torre and Koufax closed down the restaurant, having lost track of time long before.

Little did Torre know, his relationship with one of baseball's greatest pitchers was just beginning to blossom.

In the five decades since, the two have maintained an unique bond -- one shared between a baseball lifer and a man who has become of the game's greatest mysteries in the years that have passed since his Hall of Fame career ended when he was just 30, still in his prime.

Koufax, over time, has remained mainly to himself, cast widely as a reclusive hermit. But his friends unweave the mystery in a different way, painting Koufax as a genuine, classy baseball retiree who chose to live life on his own terms, not needing the public praise that many of his contemporaries still crave years after they disappeared from the glare of baseball's spotlight.

Yet, to the masses, Koufax -- outside of his jaw-dropping statistical wonders -- remains a bit of an unknown commodity.

And for Koufax, once dubbed The J.D. Salinger of Baseball, that's the way he'd prefer to keep it.

"There's an air of mystery about Sandy," Torre says. "He doesn't show up a lot of things, he doesn't need to be introduced at a ballgame or a banquet.

"Even though he's someone very special, he's grounded... But he likes his own company."

To know Koufax, say Torre and fellow World Series-winning manager Tony LaRussa, is to appreciate a man who has always been very comfortable in his own skin. Not because he has been forced to, but rather, because that's the path he has chosen to walk.

On Friday, though, Torre and LaRussa will present Koufax with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Harold Pump Foundation, which raises money for cancer treatment and awareness.

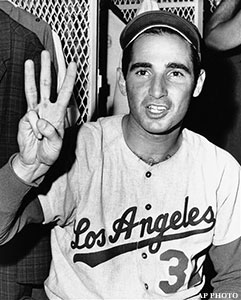

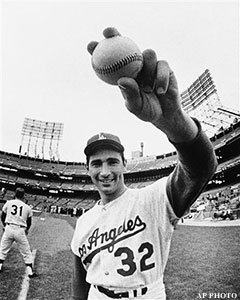

The 76-year-old Koufax will appear at the gala dinner in Los Angeles, once again being honored for just being Sandy Koufax -- something perhaps the owner of three World Series rings and four no-hitters never wanted to be singled out for in the first place.

To those who really get Sandy Koufax, however, that's just par for the course.

"He never wanted to be the center of attention -- he was never part of that ‘Dig me' generation," LaRussa says in a phone interview. "That wasn't Sandy."

Koufax entered the Hall of Fame in 1972 at age 36 -- six years after his career ended. The three-time Cy Young winner also captured the 1963 National League Most Valuable Player Award. He won 167 games and struck out 2,396 hitters -- including a then major league record 382 in 1965.

Koufax became dominant despite throwing only two pitches -- a fastball and a wicked curve ball that hitters like Torre swore they could hear the seams turning on.

Plagued by elbow injuries during his career, Koufax left baseball and evaporated from public life. After a 12-year career -- five of which he spent as a pitcher Torre says left hitters feeling like "you had just got your brains beat out" -- Koufax was gone.

"It wasn't a matter that he could win ballgames," Torre says. "He could completely shut you down."

But still, away from the game that provided him celebrity he never sought after, Koufax discovered ways to remain connected with those he trusted most. He routinely helped those who needed it while being left alone by his peers who respected his privacy.

If you called, Torre says, he was there. No questions asked.

And yet, questions about the life Koufax chose to lead chased him. People wondered why he didn't show up more or why he didn't seek the notoriety other Major Leaguers did once their careers ended.

But when you'd least expect it, Koufax would show up, pal around with his fellow former players, surrounded, LaRussa said, by an aura like none other.

"Sandy is really in a special class of one," says LaRussa, who retired last year after guiding the St. Louis Cardinals to an improbable World Series victory over the Texas Rangers. "But he doesn't need the adulation -- he's very secure in who he is and what he did.

"He enjoys his privacy and he doesn't need someone telling him he was great. He's very secure that he did the very best he could with his career until his arm betrayed him and then he kind of passed the baton to others in the game."

That's when the mystery surrounding Koufax began.

It was hard to fathom -- how a bonus baby pitching in the glamor town of Los Angeles managed to avoid the spotlight the way Koufax did. Years after his career ended, Koufax authorized a biography to be written but then refused to be interviewed. Instead, the author of "Lefty's Legacy," Jane Leavy, was left to conduct 469 interviews to find the real Sandy Koufax.

He'd pick and choose his spots, caring little how the outside world viewed him -- secure in who he was and with most of all, with being out of the public eye.

"That adds to the mystique," LaRussa says.

In a charity appearance for Torre's Safe At Home Foundation in Los Angeles in 2010, Koufax said despite all of the stories to the evidence, he doesn't consider himself someone who disappeared from society.

Instead, he told an audience of more than 7,100 that he simply chose to follow the advice of his grandfather who once told Koufax that his most precious asset in life is time.

"Spend your money foolishly, spend your time wisely," Koufax's grandfather said.

Koufax has done that mostly in private.

He is a regular at charity dinners like the annual Baseball Assistance Team dinner and has been an occasional visitor at Dodgers' spring training, always willing -- if asked -- to help a young pitcher with his craft.

Torre, who requested Koufax's presence at the event two years ago, believes Koufax has avoided the spotlight to avoid celebrity-seekers who always "want a piece of you," Torre said.

Despite the rarity of his public appearances, though, Koufax -- along with those who know him best --disputes media claims that he became a recluse.

"I don't know if I ever dropped out of sight," Koufax told Los Angeles Times columnist T.J. Simers at the 2010 charity event that raised more than $700,000 for Torre's foundation. "I go to the Final Four every year -- with 45,000 other people. I go to golf tournaments and I walk around."

Asked if he wears a disguise when in public, Koufax joked that he does by wearing a jacket.

Once again, his friends say, that's just Sandy being Sandy.

His privacy aside, Koufax has remained true to those that made up his inner circle, a group, Torre admits, that includes a select few.

For all of his charm and warm sensibilities, Koufax has always been careful with whom he trusted.

But once you were in, Torre says, you were in for good.

Koufax was among the first to call when Torre, who led the Yankees to four world championships, was first diagnosed with prostate cancer. Before Game 1 of the 1996 World Series, Torre's first with the Yankees, the skipper walked into his Yankee Stadium office and found a telegram sitting on his desk.

It was from Koufax, wishing Torre good luck.

When Torre managed the Dodgers, he'd sometimes ask Koufax to stop by to give guidance a young arm. Koufax would always call and ask if it was a good time, didn't want any part of wearing a uniform and was always happy to oblige.

Before Koufax's arrival, Torre would tell the pitcher who would be the recipient of Koufax's knowledge to pay attention.

"He was only to happy to help," Torre says. "But he really doesn't have any patience for people who really aren't interested in what he has to say."

That takes us back to 1962 and the Knickerbocker Hotel and the night when a friendship between a rookie and a future baseball legend was forged.

After spending hours talking baseball and both missing curfew, Torre and Koufax both arrived at the ballpark the next day.

Again, the two made eye contact -- this time from opposing dugouts.

"I guess I learned another rookie lesson that day," Torre says. "He was over there laughing at me knowing he wasn't going to play but I was catching."

These days, the visits or phone conversations between the two long-time friends don't take place on a regular basis. On the occasions when they do see one another, they'll talk baseball and talk life.

No longer is Torre in awe of Koufax like he was as a first-year catcher, but still, the friendship is one he values greatly, honored to be one of the select few that make up Koufax's circle of trusted confidants.

"That's the sign of a good relationship when you can pick up a phone and it doesn't matter when the last time you spoke was," Torre says. "He'll come out of nowhere and he'll call just to shoot the breeze for a while and that's it.

"But he's a special friend and I do cherish that."

Something says he's not the only one.

-- Email Jeff Arnold at jeff.arnold@thepostgame.com and follow him on Twitter @jeff_arnold24.

-- To donate to the Harold Pump Foundation's fight against cancer, click here.