At 8 p.m. ET Tuesday, Dan Rather Reports updates the profile of Daniel Rodriguez on AXS TV. Here producer T. Sean Herbert tells of the special bond between Rodriguez and his coach, Dabo Swinney, in an exclusive preview for ThePostGame.com.

On any given Sunday, you can find Clemson University's football coach, Dabo Swinney, in church. Swinney, a devout Christian, was joined in the congregation this summer by a young man who shares his passion for the gospel and the gridiron.

Daniel Rodriguez met Swinney a few months ago, and has since moved to Clemson, South Carolina.

Swinney thinks Rodriguez has a lot to offer his team that goes far beyond football.

"To have that guy in the locker room, on this campus, with these fellas when we are not around, to have him on the bus, in the dining hall, that's priceless," says Swinney. "Once he came here, I was blown away with his drive to be the best, and that's what we talk about to our team all the time: Just do your best. Just take what God's given you, and you be your best."

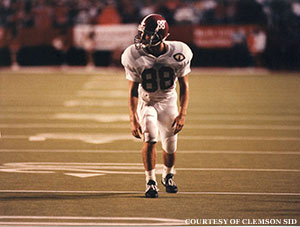

Rodriguez has been doing his best for the past two years, sculpting his 24-year-old body into perfect shape, so he can walk on and play Division I college football somewhere. At 5-8, 175 pounds, this overage, undersized war hero was a long shot at best. But the former Army sergeant has faith that he will make the grade.

"There's not a single doubt in my body that I can perform at this level," Rodriguez says. "That's the mindset I've always had."

That confidence comes from an unbreakable promise he made to a friend who was killed alongside him in a valley in eastern Afghanistan during one of the bloodiest battles in the war.

Rodriguez says of the 27 soldiers killed in his unit during battles in Iraq and Afghanistan, the death of his friend Kevin Thomson was the most difficult to emotionally overcome.

"That's what pushes me," he says. "I need to be everything I can be and more, because the air that I breathe is provided by those that have died."

On Oct. 3, 2009, in what has become known as the Battle of Kamdesh, more than 300 Taliban insurgents stormed an American outpost, killing eight U.S. soldiers including Thomson.

"He came out to get on the gun with me to start fighting. And as soon as he walked in front of me, he got hit in the head. And he dropped right by my feet."

Rodriguez was among the 22 wounded. An estimated 150 Taliban were killed and Rodriguez received a Bronze Star.

"It was written up ... heroic actions under fire and presented to me just because I didn't stop fighting," he says. "Came down to me throwing hand grenades, and killing at point-blank range."

He says despite being wounded he kept fighting because he couldn't get over the fact that Thomson was dead, and he didn't want the enemy to think they got away with it.

"I knew how many they were, but I was not going to stop shooting until it was done. And it just wasn't my day to go. And I got a medal for it."

Weeks before Thomson's death, Rodriguez and Thomson made a pledge that if they survived their combat tour, they would pursue their dreams. Thompson wanted to be a butcher; Rodriguez wanted to play college football.

"I gave him my word that I'd do everything I could to play football someday. I didn't really take to heart how serious I was gonna be about it until he was killed."

After completing his commitment in the Army, Rodriguez kept his promise. He created a video combining his unorthodox training routines with his compelling story and then posted it on YouTube last December to hopefully attract college coaches. The video went viral and caught the attention of Clemson University head football coach, Swinney.

"I just clicked on the link and was really taken aback," says Swinney. "I was mesmerized by watching what this kid had put together. Watching him physically train for just a chance. Myself, having been a walk-on, I truly understand what it's like to chase your dream."

This past spring Swinney invited Rodriguez to South Carolina for a visit.

"I took my visit down to Clemson and met with Coach Swinney, and I fell in love with it," says Rodriguez. "I just had that instantaneous connection with (what) they preach: the football team is a family."

In May, Rodriguez got a chance to prove he belonged. He received a surprise package in the mail. Clemson had sent him an acceptance letter. He jumped at the opportunity, enrolling in summer classes, while the NCAA and ACC considered a waiver making him academically eligible to walk on and play.

Swinney thought the waiver issue was a mere formality.

"When you really study his track record and the price he has paid, for him to have this opportunity to go chase his dreams, in my opinion, it was pretty much a no brainer," the coach says.

By August 1, all of the bureaucratic hurdles had been cleared. The only thing left for Rodriguez to conquer was getting his mind back into a game he hadn't played in six years, since he was a senior at Brooke Point High School in Stafford, Va.

"With camp starting, getting back in the swing of things, it's a grind," says Rodriguez. "It takes me back to basic training, where you have a time schedule. You gotta be up at this time. You eat at this time, this that and the other."

Rodriguez says surviving camp has been made easier because of the special bond he shares with his coach, whose story he finds very inspirational.

Swinney came from a home with an alcoholic father, and his parents eventually divorced by the time he reached high school. Swinney says his senior year and the years that followed at University of Alabama were very tough.

"My mom and I got evicted my senior year of high school from the town home we were renting and had to move in with some friends for a while," Swinney says. "When I moved to Tuscaloosa, that was the eighth different place that I called home in the previous four years.

"I moved to Tuscaloosa and rented an apartment with a friend. My mom moved in with me my sophomore year and was with me the next three years."

Rodriguez has had similar challenges since his junior year. First his parents separated. Then four days after graduation, his father died after suffering a massive heart attack. Like a father and a minister, Swinney, listens and takes pride in giving his walk-on a chance.

"It gives me an opportunity to give back because so many people gave to me," Swinney says. "To see a guy who's willing to pay the price, who's not asking for anything, who's willing to just work hard like everybody else, go above and beyond what everybody else is doing, that's very fulfilling. And in this case, an opportunity to give a guy a chance to fulfill a dream."

Swinney, whose Clemson Tigers are ranked in the top 15 of nearly every national preseason poll, says he shares many things in common with Rodriguez.

"I was that guy. When I chose to go to the University of Alabama and walk on, it was my dream. And I didn't want anybody to take that away from me. And I'm just blessed that I had the opportunity to make it and to earn a scholarship."

Rodriguez knows that Swinney has given him the opportunity to honor a promise he made to a fallen brother in a valley of death in Afghanistan, and he can't wait to have the opportunity to deliver in Clemson's Death Valley.

"It feels good knowing that I've done it and accomplished it for my best friend," Rodriguez says. "But at the same time, I want more. I don't want to be just a name on the sideline. My goal wasn't to be a walk on and then be content with that. Thomson wouldn't let me settle for just that."