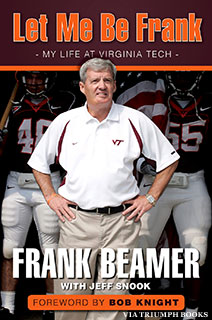

Frank Beamer has coached Virginia Tech football for 26 seasons, during which his team has enjoyed unprecedented success, including 20 consecutive bowl appearances, four ACC championships, three Big East titles and a slew of other accolades. In his new autobiography Let Me Be Frank: My Life at Virginia Tech, Beamer reveals the story of how he was tempted to leave his alma mater after the 2000 season for another coaching job but realized it would be a mistake.

Our win over Clemson in the Gator Bowl put the finishing touches on back-to-back 11–1 seasons. Dating back to our win over Alabama in the 1998 Music City Bowl, we had won 23 of our previous 25 games. Since the end of the 1994 season, we had a 58–14 record and had played for a national championship. The program was on a roll.

It was the type of success I had envisioned when I took the job.

But I learned there is one derivative of a program's success: your name is mentioned as a candidate for other coaching jobs.

I already told you about the flirtation with Boston College back in 1990 and how and why I turned down that offer. Now other people were calling me.

When we were staying in New Orleans for the Sugar Bowl following the '99 season, Green Bay Packers general manager Ron Wolf called me to set up a meeting for the following January. I agreed to meet him in Roanoke, where he had booked a room. The Packers were in the process of firing Ray Rhodes and were looking for a coach. The name "Green Bay Packers" just grabbed my attention, as it would most any coach, because I immediately thought of their tradition and Vince Lombardi.

We sat down in his hotel room that day and visited for a while, just talking football. I think he was just feeling me out and it was a very preliminary meeting. I was flattered by the interest, but I really didn't think pro football was for me. The money would have been great, but there are so many other things you have to deal with in the NFL.

Bobby Ross always told me the worst thing about pro football was that the head coach was not in control of the personnel. Our talks never got serious -- from either side.

A year later, following the 2000 season, when we were in Jacksonville for the Gator Bowl, Alabama athletic director Mal Moore called. They had just fired Mike DuBose. I wasn't much interested in that job, either, because I worried I could never do better as a coach than what the Bear had done. Any coach there would always be compared to the Bear. (Of course, as we know now, they are mentioning Nick Saban's three national championships more often than anything the Bear did years ago. It is amazing what Nick has done there.)

Another time, Vince Dooley, then the athletic director at Georgia, made overtures to me during the annual College Football Hall of Fame banquet in New York, but the talks didn't amount to anything. Only once did I ever come close to leaving Blacksburg.

In November of 2000, we had just lost that heartbreaking gameat Miami 41–21, largely because we didn't have Michael Vick and André Davis, both hobbled with ankle injuries. We bounced back to beat Central Florida in Orlando and returned home with a 9–1 record and a week off to prepare for the regular-season finale at home against Virginia.

North Carolina athletic director Dick Baddour called me, wanting to talk about the Tar Heels job. He was about to fire Carl Torbush.We talked a while and I was very intrigued with what he had to say and with the prospect of taking the Tar Heels job.

Cheryl and I wanted to get away to our house at Lake Oconee, Georgia, and Dick told us to meet him in Charlotte. We talked through a third person in Charlotte, and Cheryl and I drove to the lake house to think about our future, knowing we had an off week ahead of us. I took a few days, I talked to him again, I talked to Cheryl, and on Saturday, November 18, I told Baddour I would accept the job.

It would be one of the biggest mistakes of my life.

I didn't tell a soul other than Cheryl and my trusted assistant, John Ballein.

We prepared well and beat Virginia 42–21 the next Saturday to finish 10–1. Cheryl and I then flew to Chapel Hill on Sunday morning, November 26, to work out the details. I had totally convinced myself it was a great opportunity. In fact, I knew it was. I also knew we could win big at North Carolina. They had great facilities and support from the administration.

Once we arrived that Sunday, we toured the Dean Dome and all the football facilities and met everybody in the administration. They took me to meet the president and offered me a glass of hot cider, somewhat as a toast to the future.

I never signed a contract and they wanted me to stay that Sunday night and have the introductory press conference on Monday morning.

"No, we have to get back to Blacksburg tonight," I told them.

I know they were thinking if we got on that airplane to come home, I would change my mind.

And that's exactly what I did.

That Sunday night at my house, I got to thinking about everything. North Carolina had great facilities and great potential to win football championships to go with the many they already had in basketball. I knew we could win there. Some football coaches may have been scared off by what great basketball North Carolina always had, but I always thought that would be a plus. I never worried about basketball. What was most important to my decision-making process was the fact that those football facilities were built on somebody else's blood and sweat. They weren't built from my work.

What we had at Virginia Tech at that time, on the other hand, and what we have built for the future, were built largely because of the success we had since 1993.

Another thing was that our daughter, Casey, was in school at Virginia Tech at the time. How would she feel if we up and left for North Carolina while she was a student here? And how would she be treated if I left to take another job?

But most of all, I realized how much I loved Virginia Tech. I loved the people at Virginia Tech and the relationships we had developed over the years. I loved the town of Blacksburg. I knew that was -- and always would be -- my home. I realized there was no other place I would rather be.

I didn't sleep at all that night, weighing both sides of the decision.

"Whatever you decide, we will do," Cheryl told me. "You always make pretty good decisions."

I woke up Monday morning, or basically got out of bed since there is no waking up when you don't sleep, and I thought to myself, This is my alma mater. This is where I want to be. And this is where we will be as long as I am coaching.

I headed to the office, where everybody waited on my decision. When I walked up to the football facility, I noticed a few people carrying signs, such as "Don't Go Frank" and "Honk If You Want Frank to Stay." It felt good to be wanted.

By now, I had alerted my staff about what was happening. I think my assistants expected me to take the job even though they didn't know how far the discussions had gone. It wasn't very long after I arrived at the office when Dick Baddour called me. I didn't take the call, because I was a flat-out mess, a real basket case. I went upstairs to Jim Weaver's office and met with him, along with the school president, Dr. Charles Steger, and Minnis Ridenour.

As we talked, it became clear that if I stayed, they would offer what I wanted all along -- for my assistants to be taken care of with more money and better contracts. I received a raise, too, but my staff being taken care of was my main concern. I thought they had been vastly underpaid and that was the one issue that led me to listen when people called asking me to interview for other jobs.

I came back downstairs to my office and I called Cheryl at home.

"I can't leave honey," I told her. "We're staying."

I called all of my staff into a meeting.

"We're staying," I told them. "I just feel like I want to stay and get it done here -- not somewhere else."

At this point, Michael Vick hadn't decided whether he would return for his junior season.

"Whether Michael does or doesn't come back, it doesn't matter." I added, "I just can't leave."

I immediately felt support from all of them. One by one, they told me they would have supported me no matter what my decision was. That meant a lot to me.

Then came the hard part: I had to tell North Carolina.

I called Dick and I started my explanation, "Listen, this is nothing to do with you. It's me. I just can't leave here. I love this place and it's my alma mater. I want to tell you that you did everything right. It was perfect, but I just can't do it."

There was silence on the other end. I could tell he was upset and I understood why he would be, but he didn't say too much. He never yelled at me or anything like that. It was very cordial. He was a professional and I appreciate that to this day. Dick ended up hiring John Bunting and I think he has forgiven me over time, but it took a while. He was very cordial to me in recent years during the ACC meetings before he retired.

After the entire thing was over, I was relieved. I knew I made the right decision and I had no regrets. Not only did I not have regrets over the years, but every year that passes reinforces my belief that I made the right decision.

As a competitor, I may wonder "what if?" as far as how many games we would have won and all that. But then again, I would have wondered about the past 12 or 13 years here at Virginia Tech if I had gone to North Carolina. I also know that I just can't live my life with "what ifs" in my mind. Nobody should.

The fact is, we were in the process of building something at Virginia Tech that was very special to me and I wouldn't have been able to say that had I gone to North Carolina.

Of course, the one regret I do have is that I went back on my word. My word has always been solid my entire life and this was the one time I broke it. But I broke it for a good reason, probably the best reason: loyalty.

That is a word I mention to my coaches when we meet to begin every season in August. Be loyal to each other. Be loyal to yourself and be loyal to your school. My loyalty to Virginia Tech, and everything it stands for, won out in the end. Virginia Tech stuck with me after that 2–8–1 season and I never forget that. And I never will.

Following the 2012 season, I wanted to interview a great young assistant coach who happened to be working for his alma mater. He agreed to fly to Blacksburg and we sent the school's airplane to pick him up. As the plane sat on the runway, motor running, preparing to fly back here, he wouldn't get on it.

He called and I picked up the phone.

"Coach, I just can't do it," he told me. "Although I appreciate the opportunity and I want to thank you for it, I went to school here and I love the people here. I just can't leave."

"If anybody understands that, I do," I told him. "No hard feelings."

How could I ever be mad at him? I knew exactly what he was going through.

The North Carolina thing concluded any talk I would ever have with any general manager, athletic director, or president at any other institution. This has been my home since I arrived here as an unsure freshman quarterback in the summer of 1965, and it will remain my home until the day they put me in the ground.

I have come to determine the best things in life are sometimes right under your nose. There are no better people anywhere. And there is no better place to live than Blacksburg, Virginia.

This is my final word on the subject: I will remain a Hokie 'til the day I die.

And I can guarantee you that my word is solid on that.

-- Excerpted by permission from Let Me Be Frank: My Life at Virginia Tech by Frank Beamer with Jeff Snook. Copyright (c) 2013 by Frank Beamer and Jeff Snook. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.