No one had a clue. Not his coaches. Not his teammates. Not even his mother, looking on from her usual spot in the grandstand. On a foggy November night four years ago, Drew Rickerson found himself wandering around the sidelines of a football field in Sequim, Wash., a city of 6,600 on the state's Olympic peninsula. He was 15 years old, playing quarterback for the Sequim High varsity football team in the final game of the regular season, a week away from the state playoffs. He also was struggling to speak, dazed and disoriented, hardly able to drink water.

Minutes earlier, Rickerson had been on the field, rolling out to the right, taking on an opposing linebacker. The two collided, their helmets smashing together like bowling balls. Rickerson suffered a concussion, his brain slamming against the inside of his skull. He should have been evaluated, gone to the hospital, right then and there. A second hit could have caused more brain damage. Killed him, even. But no one had a clue. And so he stayed in the game, for a total of nine additional plays, throwing for a touchdown and running for another, the latter a 23-yard weave though multiple defenders, Russian Roulette in shoulder pads.

Rickerson flipped the ball to an official. He staggered toward his team's bench. Felt funny. On the sidelines, he stared at the overhead lights. Shapes became blurry; noises, jumbled. Four times, he sat down, stood up, then asked his coaches if he could sit back down. He dropped his helmet, picked it up, dropped it again. Over and over, he squirted water from a bottle over his shoulder, thinking it was going into his mouth. Nobody noticed. No one had a clue. Not until the game was over, when Rickerson and his teammates turned to face the grandstand. As the young men sang the school's fight song, Jean Rickerson finally got a good look at her son's face.

Usually, he would be smiling.

"She saw nothing," Drew says. "No life. I was blank. We went over to the ambulance. I don't really remember anything after that."

Football has a problem. The game harms the human brain. The danger is acute at the professional level, where large men smash each other for large sums of money; the hazard is less publicized, but greater still, at the high school and youth level, where an estimated 4.8 million children -- sons, nephews and little brothers, most between the ages of 6 and 13 -- batter each other's heads for fun, for the sheer giddy sake of sport. Once upon a time, we called football-induced brain damage getting your bell rung. We treated it with smelling salts. We kept on playing, kept on loving our Friday nights. Times change. The deaths are real. The damage no longer can be ignored. We are starting -- at long last -- to get a clue. Ours is an era of enlightenment, of concussion awareness, which is another way of saying risk management. Stories like Rickerson's -- and other stories that are much, much worse -- have spurred reform. A collective effort to make football safer. We pass laws. Change the rules. Better identify and treat the victims. Lower the odds of catastrophe. We still love Friday nights. Only looming beneath the well-meaning correctives is a darker, more troubling question, one with grave implications for the sport and the children who play it, for every parent looking on from a grandstand: What if awareness isn't enough?

What if the risk can't be managed?

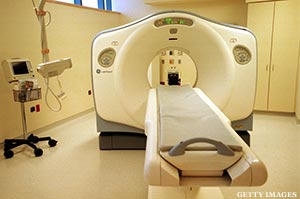

Am I being a baby? Is my mind making this up? Rickerson had to wonder. He wasn't bleeding. His arm wasn't sticking out sideways. Sequim High was going to the postseason. He badly wanted to be back on the field. Only something was wrong. Five days after being concussed -- after his coaches gave him a postgame wave and said they'd see him at practice -- he had yet to return to school. He saw stars. His thinking was muddled. When Rickerson suddenly could neither feel his limbs nor roll over in bed, he was taken by ambulance to a trauma center in Seattle, 66 miles away. CT and MRI scans of his neck were negative. A physician told Drew to go home, offering no additional instruction. Jean Rickerson sobbed the entire way back.

Drew stayed home for two weeks. He attempted to watch television, but found the experience frustrating. Who are these characters? What the hell just happened? He tried to play his favorite video game, Call of Duty, with his sister. He couldn't remember how to reload his digital rifle. His mother would take him for walks. Drew would go 200 yards before turning around. Mom, I can't do this. He returned to school, attending classes on a reduced schedule, from 8-10 a.m. He would come home exhausted, unable to recall what he had studied. Usually an excellent and attentive math student, he regularly slept through class. He would look down at the numbers on his desk and think, I know this stuff. But I can't do it right now. On Christmas, Drew went to his baseball hitting coach's house for dinner. He came down with the worst headache of his life. It lasted for an entire week.

Back in class following winter break, Drew still struggled to comprehend Dante's Inferno; a few weeks later, Jean drove him 120 miles to see a University of Washington doctor with extensive concussion experience. The doctor recommended that Drew be given a full neuropsychological evaluation. On tests, he scored in the 16th percentile. Drew no longer worried about the state playoffs, or if he was being a baby. He worried that he was going to be this way for the rest of his life.

"The doctor told me that I would be OK, but that I needed to rest my brain," Rickerson recalls. "He gave me strict orders to watch TV and do nothing. Which was OK, expect I still couldn't watch TV for a while."

Rickerson's story is hardly unique. According to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, between 4 percent and 20 percent of college and high school football players will sustain a brain injury during the course of one season; a report cited by CNN medical correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta estimates that about one in 10 high school players suffers a concussion. The Boston Globe recently reported that emergency room visits for youth sports-related traumatic brain injuries went up 62 percent from 2001 to 2009. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has labeled sports concussions "an epidemic," reported last year that roughly 122,000 youths between the ages of 10 and 19 went to emergency rooms for nonfatal brain injuries. For boys, the top cause of injury was playing football.

Disturbing as they are, Chicago-area sports medicine expert Krystian Bigosinski believes current statistics may understate the problem.

"A number of studies have compared the number of concussions athletic trainers report versus anonymous self-reported studies by players," says Bigosinski, who works at the Rush University Medical Center and is a team doctor for the Chicago White Sox, the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association and DePaul University athletics. "It's 5-10 percent by trainers, but self-reporting by players went up to like 40-70 percent had a concussion in the past season. That means you are missing nine out of 10 concussions sometimes. Someone didn't recognize the injury, or the player didn't tell anybody. That is a huge issue."

A concussion is not a bruise. It is a temporary interruption of brain function that typically occurs when rapid acceleration causes the brain to slam against the inside of the skull, often from a violent blow to the head. It may or may not accompany a loss of consciousness. Symptoms can be physical (headaches, light sensitivity), cognitive (confusion, lack of focus) and emotional (irritability, loss of interest in favorite activities). While the exact nature of the injury is not understood -- scientists know more about deep space than the workings of the brain -- some things are clear:

(a) With rest and a gradual return to regular activity, athletes who suffer a single concussion generally experience no permanent ill effects;

(b) Some athletes suffer post-concussion syndrome, in which symptoms persist for months and years, sometimes permanently;

(c) Having one concussion significantly increases the risk of suffering another;

(d) Multiple concussions are associated with an increased risk of post-concussion syndrome, as well as developing mental health problems such as depression, memory loss and Alzheimer’s disease.

Because their brains are still developing, youth football players are particularly vulnerable: According to the CDC, Ayounger persons are at increased risk for [Traumatic Brain Injuries] with increased severity and prolonged recovery." Again, multiple concussions are worse than one. Studies have found that athletes who have suffered two or more concussions experience a higher rate of mental problems -- including headaches, dizziness and memory problems -- and also are likely to suffer in the classroom. A history of concussions also is associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease found in people who have suffered brain trauma, including a number of deceased football players. Symptoms include mood swings, erratic behavior and memory lapses, followed by dementia. CTE was found in the brain of former Pittsburgh Steelers lineman Terry Long, who slid into depression before killing himself by drinking antifreeze. The disease also was found in the brain of Owen Thomas, a 21-year-old University of Pennsylvania football captain who hanged himself, and in the brain of Nathan Stiles, a deceased 17-year-old high school football player from Kansas.

A more immediate reason for alarm is second-impact syndrome, in which an athlete suffers a second concussion while still recovering from a previous one. Though the precise physiological cause is uncertain, the outcome is not: the brain swells rapidly and catastrophically, causing severe disability or death. Case in point? Jaquan Waller, a high school running back from Greenville, North Carolina, who in 2008 suffered a concussion in practice, played in a subsequent game and died after enduring a second hit. A year later, a national survey of high school trainers found that more than 40 percent of concussed athletes return to play too quickly, and that 16 percent of players who lost consciousness after being hit returned to the field the same day.

The first time Drew Rickerson heard of second-impact syndrome, he was in his neurologist's office. He thought back to the night of his concussion, the foggy conditions and the mental haze, the fact that he took nine additional snaps – snaps he could barely remember, nearly a dozen violent plays in which he somehow went untouched.

"I really dodged something," he says. "That scared the [expletive] out of me."

Jean Rickerson cried herself to sleep. Every night. For 10 weeks straight. Her son was a shadow. A zombie. Would he ever go to college? Have a job? Grow up and live a normal, healthy life? Was the damage permanent? The EMTs at the football game said Drew was fine. The emergency room staff said the same. So did a family doctor. But Drew was not fine. Jean was terrified. She felt guilty. She never wanted her son to play football in the first place. When he was 10 years old, she relented. The boy had talent. He wanted to be out there. Dad was on board. One of Jean's nieces was a drum major at the University of Florida during the Tim Tebow era; another niece worked in Urban Meyer’s office. Football was a family affair. The night her son was concussed, Jean didn't know the first thing about brain trauma. But she knew something was amiss. She could see it in Drew's body language, the strange way he was leaning over, like a listing ship. She wanted to run down to the sidelines, ask someone to do something. She didn’t want to be a stage parent. So she stayed put. Until she saw his vacant face. After that, she couldn't forgive herself. Not even when the reassuring neurologist took his first look at Drew and said ten weeks? Oh, that's not so long. Not even when the boy finally started acting like himself again.

"I went through hell," she says.

A funny thing happened when Jean stopped grieving. She started fighting, becoming a fierce advocate for Drew. For every kid like him. She didn't want to get rid of football. She wanted to make it safer, so no one would go through what her family went through. At first, she met resistance. She was thrown out of medical clinics. Screamed at during school board meetings. Chewed out by other football parents, right there on the field. Jean wanted trained medical personnel on the sidelines for Sequim High games. She was ignored. She wanted to establish a sideline protocol for potentially concussed players. She was told that was over the top. She wanted to speak to the school's football coaches about her son's injury -- a meeting that was prohibited -- and also have them trained to recognize symptoms by Dr. Stan Herring, the Seattle Seahawks team doctor, a member of the National Football League's Head, Neck and Spine Committee. After all, Drew hadn't been knocked out on the night of his concussion. But he had been struggling to speak and sporting asymmetrically dilated pupils, two classic signs of brain trauma. His coaches never noticed. "They were untrained," Jean says. "At the time, they didn’t have a level of understanding."

Jean arranged a meeting with Dr. Herring, invited 200 people to attend, including local parents, pediatricians and EMTs. The night before the meeting, she learned that Sequim High's football coaches and players weren't planning to show up. She was furious. She drove into town, parked her car in a school lot and waited for the local school superintendent to emerge from a graduation ceremony. She waited. And waited. She went inside, walked up to the dais and told him: We have a problem. The calls went out at 10:30 p.m., to coaches and players. The next afternoon, everyone was there. No one would speak to Jean. She didn't care. "I never thought of myself as a stalker," she says, "but that's what it took. It made a tremendous difference." She kept pressing. At the school's away games, she made sure the EMTs on hand knew something about concussions, made sure they had a life flight catastrophic injury evacuation plan. Just in case. Through the parent grapevine, she began to learn which players on opposing teams were coming back from concussions. She tipped off the EMTs, told them to pay extra attention.

One night, Jean saw an opposing player stagger around after a hit, unsure of which bench was his. She went down to the sidelines, approached the opposing coaches. Did you take a look at your player? Are you aware of state law? No problem, they told her. No problem. After the game, Jean found the boy's parents outside the locker room. They were grateful. This is not his first concussion, they told her. We don't know what to do. And that was the whole point. Jean recalled what a Sequim High athletic official told her, 10 months after Drew's utterly mismanaged concussion.

"We didn't know," he said, "what we didn’t know."

Rickerson will be the first to admit: When it comes to brain trauma in high school football, risk reduction is hard. And painful. There is no magic bullet. There are simply a series of hedges, each a flawed and imperfect fix, none of them cheap or easy to implement, most an affront to the game’s macho culture. A Washington state law named after Zackery Lystedt, a middle school football player who suffered permanent brain damage after suffering a concussion and returning to play, requires that players who show signs of being concussed be removed from games or practices and not be allowed to compete again until being cleared by a health care professional trained in concussion evaluation and management. Thirty-one states and Washington, D.C. have adopted similar laws; the NFL and NCAA have lobbied lawmakers in 19 other states to enact similar legislation. Return-to-play laws are a good first step, but hardly a comprehensive solution. They do not require the presence of trained medical personnel at practices or games, reportedly because that would be too costly for many rural communities. They do nothing to address one of the key problems in concussion risk reduction: Diagnosing the actual injury. According to the National Athletic Trainers’ Association, only 42 percent of high schools nationwide in 2010 had access to a certified athletic trainer educated in concussion care; numbers for junior varsity, middle school and youth squads are unknown, but likely lower still. Moreover, football players hide injuries. They don’t complain. They try to play through. Such is the ethos of the sport. Last December, the Associated Press surveyed 44 NFL players, a cross-section of the league; 23 of them said they would try to conceal a possible concussion in order to stay on the field. Youth players are no different than their professional idols. "We train our kids to expand their pain threshold, to fight through things," says Chuck Willig, a high school football coach in California for more than 20 years. "But we have to get them to understand the severity of [brain injuries]. We're trying to take away the idea that it’s about weakness, trying to decriminalize the mentality of 'being soft.' That is really hard."

Safety efforts also face legal hurdles. According to the New York Times, Boston University researchers offered in 2010 to staff every game and practice of a Massachusetts youth football league with a trainer to watch for concussions and arrange for treatment. They were turned down due to administrative issues. Jean Rickerson put together an computerized concussion testing program for five school districts in the Olympic Peninsula. The program was independently funded. The district’s risk management department turned her down. The reason? A counterintuitive liability trap that wouldn't be out of place in "Catch-22." "Suppose you're a high school, and you obligate yourself to neurological testing," explains Chris Callanan, a Boston attorney with expertise in sports injury liability law. "God forbid you do it wrong and put a kid back out there who gets seriously hurt. Now you've opened yourself up to serious liability." In 2009, Philadelphia's La Salle University paid $7.5 million to settle lawsuit brought by the family of Preston Plevretes, a football player who suffered a severe brain injury in a 2005 game following a mismanaged previous concussion. The school admitted no wrongdoing. It no longer has a football program.

Despite the best efforts -- marketing and otherwise -- of equipment makers, there is no forthcoming technological tourniquet for football's concussion crisis. No magic mouth guard. No space-age super helmet. Helmets prevent skull fractures. They do not prevent the brain from moving inside the skull. Think of the skull as an eggshell, the brain as a yolk. How much yolk protection does a Styrofoam egg carton provide? Testifying before a Congressional committee last October, American Academy of Neurology sports section chairman Jeffrey Kutcher admitted as much, stating "I wish there was such a product [that could prevent concussions] on the market. The simple truth is that no current helmet, mouth guard, headband, or other piece of equipment can significantly prevent concussions from occurring."

ImPACT, a computerized concussion identification and evaluation tool used by many professional sports teams and increasingly deployed at the high school level, is costly, controversial and arguably flawed. A 20-minute series of cognitive tests given on a computer screen, ImPACT supposedly helps diagnose the severity and duration of brain trauma, which in turn helps determine when a player can be allowed back on the field. Problem one: A baseline preseason test is essential, but as San Francisco-based reporter and concussion gadfly Irv Muchnick has pointed out, ImPACT marketing materials claim otherwise. Problem two: Players have been known to cheat on the actual exam, both by sandbagging their baseline scores and popping Ritalin in an effort to score higher. Problem three: According to Slate magazine, two recent studies examined the usefulness of ImPACT and concluded it has very little practical value, with one study claiming that the test's reliability is "unacceptably low." Robert Sallis, a physician and past president of the American College of Sports Medicine, told Slate that ImPACT was a "huge scam."

Last December, Steelers defensive lineman James Harrison sent Browns quarterback Colt McCoy airborne with a vicious helmet-to-face mask hit. McCoy was concussed. No one realized it. The quarterback reportedly was lucid on the sideline, only complaining about a bruised hand. He sat out two plays and was evaluated by a team trainer, who declared him "good to go." McCoy played a total of 18 additional plays. Like Drew Rickerson, he could have been killed. While showering after the game, McCoy began feeling unwell; before giving interviews, he asked that television camera lights be dimmed. Watching the game on television -- the severity of Harrison's hit was obvious on replays -- McCoy's father, Brad, was incensed. A longtime Texas high school coach, he publicly condemned the Browns for not examining his son more thoroughly before sending him back on to the field. The incident touched off a media firestorm, with the NFL moving to place certified athletic trainers in above-field press boxes to watch for missed concussions and NFL Players' Association executive committee member Scott Fujita calling for the sideline deployment of independent neurologists. Watching the story unfold, Muchnick pondered the implications for youth football. "High schools and pee-wee leagues can't possibly do what the NFL does," he says. "Every youth program in the country can't have replay review and coaches in headsets at the press box level. Nor can every youth program have a Medivac helicopter and a sideline neurologist at its disposal for every single game, every single practice."

And?

"Long term, I think football is screwed."

Even now, Drew Rickerson regularly watches his old high school game tapes. He is 18 years old, a freshman at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, on track for early graduation next year with a physics degree. He plans to transfer to a larger school to study engineering. He is smart and healthy. He still plays Call of Duty. He misses football like crazy, calls the sport the love of his life. When doctors cleared him, he returned to play his junior and senior seasons. At first, he was scared. He stopped hurling his 170-pound frame into oncoming linebackers, started running out of bounds. After enduring a particularly hard hit his junior year, he went straight to the sideline to request a concussion test. Drew was unharmed. He was lucky. He knows it. One Friday night following a game, he saw a teammate in the locker room, lying on a bench, sleeping in his uniform. Early the next morning, Drew returned to watch film. His teammate was there, still in his shoulder pads. "He couldn't drive home," Drew says. "I felt so bad. He just wanted to play, didn't want to tell anyone that his head hurt."

A concussion is not an automatic death sentence. Brain trauma does not always produce lasting damage. Football can be made safer. But the sport exacts a cost. A 2009 study found that former NFL players are diagnosed with severe memory related diseases at nineteen times the rate of the general population. Evidence suggests that CTE -- the silent killer, the disease that turns players' brains into ticking time bombs, slowly driving them mad -- is caused not only by concussions but also by sub-concussive trauma. Little hits. Little hits like the 1,000-1,500 blows to the head that the average high school football lineman absorbs in a single season, according to estimates by Boston University researchers. When Purdue University researchers recently compared brain scans of concussed and non-concussed football players, they were shocked to find brain changes -- read: damage -- in both. They thought their scanners were broken. No such luck. The good news? The observable brain changes appeared to subside in the offseason. The bad news? The researchers don't know exactly what that means, or if the same brains suffered permanent harm. One of the researchers, Eric Nauman, said he would never allow his child to play football. Former New York Giants Hall of Fame linebacker Harry Carson, who suffers from post-concussion syndrome and estimates he was concussed more than a dozen times during his pro career, says that he wouldn't have played football if he had known what the sport would do to his brain. Two years ago, Carson's youngest son, Kip, reportedly tried out for Auburn University's football team but failed a physical exam when doctors discovered elevated blood pressure. Carson was happy; he didn't want Kip to play. Last year, concussion expert Robert Cantu told the Boston Globe that children under 14 should not be allowed to play collision sports unless those activities are modified to eliminate head blows. "It doesn't make sense to me to be subjecting young individuals to traumatic head injury," he said. "There's no injury that's a good one, and you can't play collision sports without accumulating head injuries." Before the Super Bowl, the Sports Legacy Institute -- an athletic brain trauma education and advocacy organization co-directed by Cantu -- released a white paper proposing the adoption of a "hit count," by which athletes under 18 would be prohibited from enduring more than an agreed-upon number of blows to the head during a particular period of time; as a starting point, the SLI suggested no more than 1,000 hits in a season, and no more than 2,000 in a calendar year.

"I -- and others -- have a better idea," Muchnick says. "End tackle football in public high schools."

Willig disagrees. He cares about young people. And safety. He also loves the game. The 51-year-old high school coach is a lifer. As a high school senior, he set a California single-season interception record; at Northern Arizona University, he was an All-American. Willig has six brothers who played the game, three at major colleges, one for 14 seasons in the NFL. He values what the sport can teach: Discipline, teamwork, toughness, sacrifice. Friendship and love. Over 25 years, he has coached hundreds of young men. He still keeps in touch with many. "As high school coaches, we're charged with a much greater obligation to these kids than, let's say, the NFL is," he says. "This is something that needs to be taken to great, painstaking lengths with parents, kids and coaches. If people feel the risks are too great, there are other sports kids can get involved in that offer the same benefits. I’m a little partial to football. I don’t want to see us abandon a sport that has so much to offer. Our culture is built on being able to learn about risks and decide for ourselves whether to take them. It's like almost anything else that we do. Do I drive a car with the risk of having an accident and getting killed?"

Watching her son play football again was the hardest thing Jean Rickerson has ever done. Truth be told, she didn't even want him driving a car. Every bump on the road made her shudder; every hit on the field made her cringe. But like Willig, she loves the sport. Loves Drew. Couldn't bring herself to say no. She currently runs a website, sportsconcussions.org, which advocates for young athletes and acts as an information clearinghouse. She knows a girl in Massachusetts who suffered seven sports concussions and had to home school. A football player who dropped out of an Ivy League college after suffering two concussions -- the later of which left him unable to even run track. She knows families whose children have been dealing with post-concussion symptoms for more than four years. "When you are 16 and suffer this, it changes the path of your life," she says. "It's not just you can't play on the teams you want to play on. It's that you can't go to college. Can't get a job. This is a tremendous problem. It changes entire families. I was lucky."

On a Friday night last September, Jean watched in horror as six different Sequim High football players were concussed in a single game. Four of them went to a nearby hospital. There were four ambulances on the school's football field at the same time. "The medical professionals were shocked," Jean recalls. "Many in the community were shocked. I thought to myself, I'm one person with one snapshot of this issue. If what I'm seeing is being replicated across the country, then we're still in trouble."

Willig has a point: Life involves risk. But the brain trauma inherent to football is not accidental. It's intentional. The game is violent by design, a demolition derby in a world of traffic lights and stop signs: A recent Virginia Tech study of a group youth football players -- ages 6 to 8 -- found that the average boy endured 107 hits per season, and that some of the hits were as physically forceful as those found in college football. The whole point of the sport is to hit another human being as hard as you possibly can, and in that sense, football has less in common with driving than with smoking cigarettes -- another popular, socially unnecessary activity that feels good but causes physical harm. Recently, Jean asked her son if he ever worried about how playing football might affect his mental health thirty years from now. Drew was stumped. He had never really thought about it. "I was pretty much a kicker with a [throwing] arm," he says. "I didn't take a lot of hits. I think I'll be OK. But yeah, it could affect me. There's nothing I can do now. It's rolling the dice, I guess."

Protect our national pastime. Protect our children's brains. The hope is that we can do both. Biology and physics suggest otherwise. Safer does not mean safe. In locker rooms and school board meetings, quiet funerals and noisy grandstands, the future of youth football may not be matter of risk management. It may be a matter of risk acceptance. Roll the dice.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- Jeremy Lin's Middle School Yearbooks Hit eBay

-- White Star, Black School: Landon Clement Is The Face Of Upstart North Carolina Central

-- Jeremy Lin's No. 17 Jersey Is NBA's Top Seller

-- Jeremy Lin A Superstar? This Man Saw It Coming