Lisa McHale has every reason to be happy. Awareness of football's inherent concussion risks has taken root among much of the U.S. population, parents are thinking twice about letting their kids play football, and even college and professional players are taking a second look at their own involvement.

Compared to this time last year, so much has changed. For McHale, though, it's just one small step in a much larger process.

"Just the general awareness that concussions are an issue, that is certainly much more recognized," McHale says. "There needs to be much more done, however, educating [the public] on what that means."

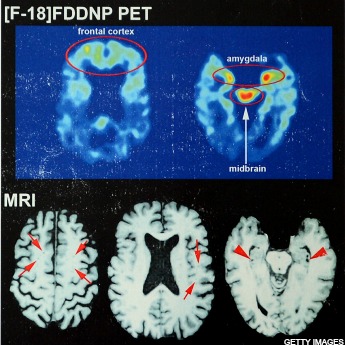

McHale has unique perspective in observing the cultural change regarding concussions in sports. As director of family relations for the Sports Legacy Institute, she is in constant contact with families who have chosen to donate brain tissue samples to the brain bank at Boston University. The bank functions as the world epicenter of diagnoses and research regarding chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE -- the condition that degenerates brain tissue through the build-up of protein, and which is caused by often repetitive damage to the brain.

McHale is perfectly suited to deal with families who have lost loved ones suffering from CTE. Her husband, Tom McHale, was a former NFL player who died in 2008, and who later became one of the first NFL athletes diagnosed with CTE.

When her husband passed away, Lisa McHale knew nothing about the disease. Even more perplexing, she wasn't aware of Tom McHale suffering concussions either during his college career at Cornell or during nine seasons in the NFL.

"It was very much news to me at the time," Lisa McHale says. "Nowadays, people are much, much, much more aware of it. It's not uncommon for donors to reach out to us, instead of us trying to track them down."

Indeed, much has changed -- both in terms of the general public's knowledge as well as how researchers perceive of the disease. When Tom McHale was the sixth former NFL player diagnosed with CTE, the condition was seen as causing dementia during an individual's 40s and 50s. In 2008, CTE had been identified only in NFL veterans between ages 36 and 50.

Since then, brain bank donations have skyrocketed -- a benefit of families being able to recognize some of the symptoms of the disease. CTE has been diagnosed in many younger individuals, including former football players who never even competed beyond the high school level -- Boston University's CTE Center lists an unnamed male donor -- a multi-sport athlete who suffered multiple concussions -- as its youngest brain donor diagnosed with CTE. That individual was only 18 years old.

Bear in mind, CTE can only be diagnosed after an individual dies. The diagnosis of CTE in one deceased 18-year-old makes it very likely that the condition is affecting other teenagers, potentially even minors.

And with that comes great risks. Death is often the end result of a long, grueling stretch of suffering by patients with CTE. Tom McHale's post-NFL years were fraught with behavior that was later much easier to attribute to CTE. His wife told The New York Times that in 2005 -- 10 years after his retirement from the NFL --McHale began abusing painkillers to deal with chronic pain resulting from his football career. The use of these medications exacerbated lethargy and depression he had already been exhibiting.

Tom McHale went on to start using cocaine, and he entered drug rehab three separate times. On May 25, 2008, he succumbed to what had plagued him, accidentally overdosing on a combination of cocaine and the painkiller oxycodone.

That drug behavior didn't mesh with who McHale had been the rest of his life. The erratic made much more sense when placed in the context of his CTE. The condition can have different effects in different individuals, but common complications can include depression, anxiety, short-term memory loss, confusion, and even suicidality. It's normal for these symptoms to first show up years, sometimes decades, after the last involvement in sports.

Tom McHale's diagnosis was part of an early jolt of momentum that first thrust the issue of CTE into the sports spotlight, and subsequent diagnoses continued to increase awareness of the condition while cluing researchers in to how CTE comes about.

The trends uncovered by recent research are even more disturbing than what researchers thought seven years ago. We now know that concussions even in adolescence and youth can yield serious consequences later in life. But it's not only concussions that athletes and their loved ones need to worry about: Several studies over the past few years have pointed to sub-concussive hits as being just as problematic and dangerous. They're also tougher to identify than a traditional concussion, which increases their threat.

Meanwhile, a large study published last month in JAMA argues that those big hits garnering replays during TV broadcasts are just the tip of the head injury iceberg. Most football concussions, according to researchers, occur in practice -- not in games.

That's why McHale isn't content to celebrate our collective public awareness of concussion risks. Even as the general public gets informed on the issue, new evidence is presenting an even more alarming picture -- and fully understanding the threat against our mental health is critical to making any real progress.

"There's a lot of false sense of security that people know more than they do," McHale says, "as far as translating to the playing field, catching concussions when they occur.

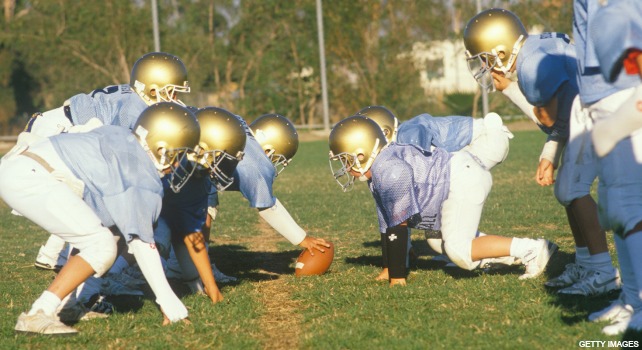

"it's a real question of, well, what do we do about that? People do need to be aware of how much our kids' brains are getting jostled about."

McHale's preference would be for contact to be eliminated from practices. That would eliminate a huge chunk of concussions suffered at the college level and below, not to mention the sub-concussive hits sustained on a daily basis.

She also thinks football should be limited only to athletes high school and above. Below that age, kids are taking too much contact on their heads and don't understand how to protect themselves. The full risks of such a sport, meanwhile, can't be easily communicated to a seven-year-old.

But you can teach a young player how to identify signs of a concussion -- and she doesn't see why that can't happen on a national scale.

"If we can give kids a red ribbon to say 'No' to cocaine and heroin, I think we can tell them that head trauma is bad, and that if it happens, they need to tell an adult," McHale says.

One of the biggest cultural events pushing concussions into the public spotlight was the rash of college and NFL players who left the sport during the current offseason. The most significant such retirement was by San Francisco 49ers linebacker Chris Borland, who was coming off of a very impressive rookie season but decided the sport was not worth the long-term health risks.

Borland was just at the start of a potentially lucrative NFL career, and quitting when he did forfeited millions in potential earnings. When he retired, Borland emphasized his concerns over concussions and brain injuries football would exposure him to, and he couldn't justify playing the game even with so much money on the line.

Several other NFL players, including Tennessee Titans quarterback Jake Locker, retired either in their playing primes or with several productive years ahead of them. Some were more specific than others about why they were quitting, although the wear and tear of the game was cited by most. And in the college football ranks, Michigan center Jack Miller chose to give up his senior year rather than put himself at another year of risk.

Such defections from football show that public awareness is affecting change even at the highest levels of play. This is perhaps the capstone of brain injury awareness to date: As individuals gather more information about what could happen to them later in life, they're less willing to sacrifice their futures for the sake of a sport.

The criticism against the NFL's early handling of concussions was that it withheld information about the true risks the sport posed to players. Now, that information is widely available -- even mothers of small kids have access to an abundance of information. The public's awareness is critical in spurring on any change, whether that change is cultural or regulatory.

Both the NFL and college football have committed to increasing the safety of the game. The college game moved up kickoffs to reduce the rate at which kicks were returned -- kickoffs being the most injurious play in the game, statistically speaking -- and the NFL has implemented a strict concussion protocol while levying harsh rules and punishments for head targeting of players.

Player safety is being addressed by the sport. But concussions remain an inevitable risk -- and CTE looms in the distance.

"I don't know if it's enough," McHale says of the NFL's safety reforms. "They have absolutely done some things to make the game safer. Whether it's enough, I really don't know.

"But I think with the NFL I'm less concerned, because it's a game for adults. As long as they're aware of the risks, then I'm OK with that."