As teams pursue a playoff position and a World Series title in the second half of the baseball season, the most important name in the sport might not be Mike Trout, Miguel Cabrera, Clayton Kershaw or Adam Wainright. The name with the most impact might be Tommy John.

Tommy John has become shorthand for Tommy John surgery. The operation, named after the pitcher who had the first such operation in 1974, is a procedure in which the damaged ulnar collateral ligament in the elbow is reconstructed using a tendon from another part of the body, usually the forearm. The tendon is used to re-create the damaged ligament and improve the stability of the elbow joint. After the surgery, it usually takes about a year for a player to be ready to pitch again.

This season, a small army of young arms have been lost for the year because of the injury.

The list includes the Tigers' hard-throwing reliever Bruce Rondon, Patrick Corbin and David Hernandez of the Diamondbacks, Jose Fernandez of Miami, the Rangers’ lefty Pedro Figueroa, Braves reliever Corey Gearrin, Athletics righty A.J. Griffin, the Royals' Luke Hochevar, Rays lefty Matt Moore, the Yankees’ Ivan Nova, and the Mets’ Bobby Parnell.

Some pitchers have needed the procedure for a second time. That group includes Rockies right-hander Tyler Chatwood, Kris Medlen and Brandon Beachy of the Atlanta Braves, Daniel Hudson of the Arizona Diamondbacks, Corey Luebke and Josh Johnson of the San Diego Padres, Jarrod Parker of the Oakland A's.

The Yankees rookie phenom, Masahiro Tanaka, is the latest candidate for the procedure.

While trying to stay in the playoff hunt, New York will have Tanaka rehabilitate the relatively small ligament tear, with the long odds that he can avoid a Tommy John.

Baseball experts are still trying to sort out the possible reasons for the surge in the surgery, which has about an 85 percent success rate.

Rick Peterson, the Baltimore Orioles' director of pitching development, cites three main reasons for the rising amount of ligament damage: Increased velocity, too many innings before becoming pros and defective pitching motions.

"Velocities are way up to what they’ve been over the years," he said.

According to Peterson, the force needed to generate that much speed pushes tendons and ligaments to the limit.

“You have many more guys who are throwing 100 miles an hour or close to 100,” said Peterson, a coach for 35 years and the founder of 3P Sports, a program to study and prevent injuries among amateur and professional pitchers. "Guys are throwing so hard now that ligaments can only handle so much force and torque and speed."

Peterson feels that pitchers have been overused at the amateur level, including playing on travel teams, and throwing too many innings and playing all year long with not enough breaks.

"Years ago, I had a pitcher that needed Tommy John surgery," he said. "We had a biochemical analysis of that pitcher. His delivery was flawless. He was in great physical condition. And yet a year later he had Tommy John. He was abused in college. When he had the surgery, when I talked to Dr. (James) Andrews, who was the surgeon, he said, ‘I just operated on a 40-year-old elbow.'"

In addition, defects in deliveries contribute to pitchers' hurting their arms.

"If there’s a major flaw, you’ll be injured,” he said. “That’s just a given."

Dr. Ralph Gambardella, a surgeon and chairman and president of the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in Los Angeles, has been performing Tommy John surgery on players from the Pony Leagues to the majors since 1985. He said there are numerous factors involved in the arm injuries.

"It's multifactorial,” Dr. Gambardella said about ligament tears. "You are going to see more and more in the world about genetics, and genetic screening. Maybe to the point of supposedly picking the sport your 2-year-old is going to decide to go into. However, it's not as easy as that. There are so many variables that are involved here that it gets very difficult to really come up with the best way to prevent injury to the ligament.

"It's like a spike, just like the weirdness of the winter weather around the country. Is there some overall thing going on? If so, we haven’t been able to quite figure it out. I think that people spend more time conditioning in the off-season then they ever had. So it’s hard to put your finger on it. I don’t think we can blame one thing."

Dr. Gambardella believes teams are diligent in monitoring pitchers year round.

"Each team has their own program, and they try to keep a watch on their own players,” he said. “There’s been a lot of controversy over whether or not, for example, players should play winter ball or not play winter ball. Is it better to give them a long rest or a short rest?”

As far as the growing number of pitchers who need the second Tommy John surgery, Dr. Gambardella again feels genetics plays a role.

"The basic problem is the original ligament is the best," Dr. Gambardella said. "The reconstructed ligament is going to be no better than the original. The forces that go through it are the same forces that tear the original. We have not solved the problem of how to heal a ligament biologically and get it back to its original state.

"At this point, even if we do that, we still haven't solved the problem of what can we do preventively to decrease the number of these injuries. Because the ligament is clearly getting overloaded from the act of throwing."

Peterson believes that players might feel invincible after the first Tommy John procedure. That leads to a false sense of security and the chance for re-injury.

"This notion that you get a Tommy John surgery and you're good for life,” Peterson said. "Let’s say the first one was the result of a combination of a flawed delivery and overuse. The question is have they made an adjustment in their delivery when they come back?"

One theory among the medical community is that some people have genetically stronger ligaments and tendons. In that case the original ligament would be less prone to tear. Pitchers who require Tommy John surgery who have a genetically stronger donor tendon used to replace the torn ligament may need only the one procedure.

Another aspect physicians and teams are reconsidering is the rehab time. Most pitchers return to action nine to 12 months after surgery, down from the original 12 to 18 months. Do the players need more time to recover?

"Historically, the longer rehabs were chosen because we did not really know where we were going," Dr. Gambardella said. "I think that what happens here is that biologically, because the tissue has to transform and then become a ligament, the only way it does that is being subjected to small incremental increases in stress, which is why you go through an extensive throwing program. Clearly, if you just want to make it easy, then have major league baseball come up with a rule that says nobody can throw a ball faster than 85 miles an hour. Then you don’t have a problem anymore. When people rehab from these surgeries, the only time they start to get into issues is when they're rehabbing in the final stages. And that's when we're putting those excessive stresses on the reconstructed ligament or on the original ligament."

Dr. Gambardella feels that biology, along with nutrition, holds the key to optimal recovery from Tommy John surgery. He also believes that as medicine advances the procedure will not be needed.

"We're getting back down to the biology," he said. "Even when the ligaments are just starting to fatigue, and there may be microscopic injuries that occur to the tissue, can we do anything to enhance the healing response? That's part of what you’ve seen with everything that’s gone on with P.R.P. injections, and regenerative medicine, and adding stem cells."

Platelet rich plasma injections, or P.R.P., use part of the patient’s blood to promote healing of injured tendons, ligaments, muscles and joints. The Yankees' Tanaka is using this procedure to try to avoid surgery.

For medial collateral ligament injuries, Dr. Gambardella said, “there may be a role for treatment with P.R.P. and stem cells that can allow people to actually get back without having to go through the Tommy John procedure."

"So I think the biology of healing includes diet, exercise, nutrition, all of those factors,” he said. "Our problem is we haven’t been able to figure out the right combination yet."

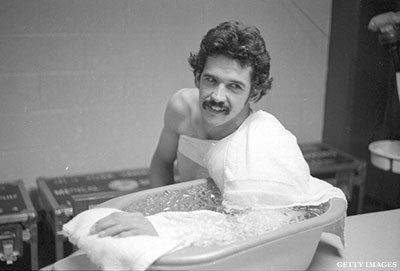

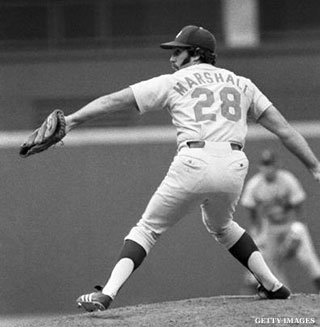

Dr. Mike Marshall, was a successful relief pitcher who won the Cy Young Award in 1974 with the Dodgers. He holds two major-league records: 106 pitching appearances in a single season in 1974 and 13 straight appearances that same year. He believes the way pitchers deliver the ball is the main culprit in injury and ulnar collateral ligament damage.

Dr. Marshall has a Ph.D. in exercise physiology, coaches athletes and offers advice on his web site, DrMikeMarshall.com.

"The ulnar collateral ligament is a ligament, not a muscle," he said. "Only muscles are able to hold the elbow joint tightly together."

He endorses a pendulum swing in pitchers' motions that uses muscles to eliminate stress on the ulnar collateral ligament.

"Pitchers need to pendulum swing their arm downward, backward and upward to driveline height in one, smooth, continuous movement,” he said. “Such that their upper arm is at shoulder height, their forearm points backward with their hand slightly above their head. This position forces pitchers to contract the muscles that protects the ulnar collateral ligament.”

Driveline height is the horizontal height at which baseball pitchers drive their pitching elbow toward home plate. Dr. Marshall predicted that the Marlins' Fernandez and Tanaka of the Yankees would be candidates for Tommy John surgery after analyzing their deliveries earlier this season. Fernandez had the procedure May 16, and Tanaka is disabled with a ligament tear and might eventually need surgery.

He gave a scouting report on the pendulum swings of a few selected pitchers.

He believes the Tigers' Justin Verlander and Max Scherzer "have very good pendulum swings."

However, he cautions that the Dodgers’ Clayton Kershaw does not pendulum swing his arm to driveline height in one smooth movement.

Instead, Dr. Marshall said of Kershaw and pitchers with similar deliveries, "They stop their arm just behind their body, then, with their forearm pointing downward, they raise their forearm to pointing upward. From this position, they pull their elbow forward, which reverse bounces their elbow and does not contract the muscles that protect the ulnar collateral ligament. These pitchers are candidates for tearing their ulnar collateral ligament."

Dr. Marshall's theories, like several others, will be considered by a baseball community searching for answers to save their young arms.

-- Joe Brescia is on staff at The New York Times.