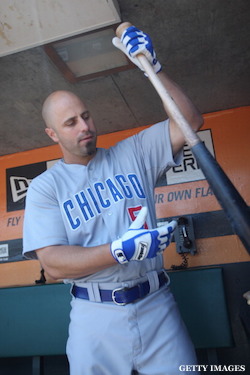

Reed Johnson wasn’t ready.

The veteran outfielder had just begun to stretch when he learned he would be pinch-hitting for Cubs pitcher Jeff Samardzija to lead off the sixth inning of a game against the Brewers in May 2012. He grabbed a bat and walked to the plate cold.

Looking for any way to get loose, Johnson lunged at Marco Estrada’s 1-0 pitch in the dirt and missed. But the next offering zipped right down the middle, and Johnson clubbed it over the left-field wall.

Now a key member of the Marlins’ bench, Johnson remembers that at-bat not for its success -- he knows he got lucky -- but as an example of what not to do.

“If I’d have used that preparation to guide me for the rest of my career, I’d probably be in big trouble right now," he said.

The nature of hitting is to prepare tirelessly and fail frequently. Even if a fat pitch can help reverse those cruel dynamics on occasion, pinch-hitting more often magnifies them, all that preparation funneled into one chance.

"You're like, 'God, I hit like a thousand balls and I go out there, strike out, and my day's over,'" Johnson said.

Johnson has made the second-most pinch-hitting appearances of any active player and posted numbers nearly identical to his career stats. This, too, bucks a persistent overall trend. In 2013, for example, while the league as a whole batted .253 with a .318 on-base percentage and .396 slugging percentage, pinch-hitters posted a line of .217/.292/.336. A similar divide exists this season.

The job demands a lot. Pinch-hitters must ready themselves physically and mentally for an at-bat that could come at any moment -- or never. Not all hitters are capable. Not all are fully willing. Those who are both might seize an opportunity to extend or expand a career.

For Matt Stairs, the turning point came when he moved to the National League in 2001, joining the Cubs. By the time his career ended in ‘11, he had racked up nearly 500 regular-season pinch-hit appearances and set a still-standing record of 23 pinch home runs, not including his memorable blast for the Phillies in the 2008 NL Championship Series.

“The day I knew I wasn’t gonna play every day, I accepted it and wanted to do it and I looked forward to doing it,” said Stairs, now a Phillies television broadcaster. “I wanted to be that guy that could come in and be that game-changer in the eighth or the ninth inning.”

That’s the attitude Rangers hitting coach Dave Magadan now preaches after a 16-year career he bolstered with a .382 OBP in 421 pinch-hit appearances.

“I think the guys that struggle with it are the guys that fight it," Magadan said. "They don't see it as an opportunity to go 1-for-1. They see it as an opportunity to go 0-for-1."

Of course, embracing the challenge isn't the same as conquering it. Willingness must be backed with labor, and for most pinch-hitters, there's plenty of that.

Getting ready for a pinch at-bat is a complicated dance that can involve stretching, swinging, studying and reading a variety of cues about game situation – all orchestrated to generate peak performance within a tiny window. Timing is critical.

“If you’re getting ready the whole game, then you’re going to be out of gas, so it's a fine line between being ready and wearing yourself out,” said the Reds' Chris Heisey, who had eight career pinch homers, with a .935 OPS as of Friday. "You’ve got to kind of know the limit and then at the last second get up to game speed."

From Little League through the minor leagues, most big leaguers play every day and gain little to no experience in this art. As veteran bench player Greg Dobbs put it, going from three to five at-bats per day to maybe three to five per week requires making good use of the time not spent in the game so that when opportunity knocks, "you don't feel like everything is so fast." Learning this comes from trial and error and often the guidance of veterans, who pass their tips and tactics down to the next generation.

After Dobbs debuted with the Mariners in 2004, he soaked up knowledge from Dave Hansen, who is fourth all-time in pinch-hit appearances (703) and sixth in hits (139). A decade later, Dobbs -- now at the Nationals' Triple-A Syracuse affiliate -- sits as the active leader in both categories, thanks in large part to a routine shaped in those early days.

“I’ve learned that you have to prepare more than anyone,” Dobbs said while playing for Washington earlier this season.

He will start well before the game, looking at video and scouting reports of pitchers he might face and studying their past confrontations. Once the game is underway, Dobbs stays on the bench, supporting his teammates and watching, with a purpose. He looks for little things -- such as how the opponent is attacking his team's left-handed hitters -- to file away for later. Then sometime between the third and fifth innings, he begins getting his body ready while also tracking pitch counts for both starters and thinking about matchups, looking for a spot that might require his services.

As the Marlins' Jeff Baker described this game of mental gymnastics, “You basically become your own manager to make sure you’re not surprised by the situation when it comes up.”

The routines vary from player to player.

Like Dobbs, Johnson craves information, believing it can “lower your anxiety.” His iPad is loaded with scouting reports and video of pitchers, and before each series, he studies intently, looking for tendencies and developing a plan. During games, he leaves the iPad in the tunnel between the dugout and the clubhouse in case he needs to grab it for a quick refresher before an at-bat.

On the other end of the spectrum, Heisey mostly foregoes any information beyond what the pitcher throws.

“I try to stay away from video,” he said,. “If I try to look for too many tendencies, I’ll start guessing up there, and I’ve never been a good guesser.”

Instead, Heisey’s focus rests on making sure he’s “ready to attack” when he steps to the plate, alert for a potentially meaty first-pitch fastball. While some hitters like to work the count more than others, there is a balance to strike between waiting for an optimal pitch and not exacerbating an already difficult situation by inviting an adverse count.

“The best pitch you get might be the first one,” Magadan said. “It's hard enough to pinch-hit without always being 0-1 all the time.”

But before a pinch-hitter can worry about when to swing, he must prime his body for the task. That means getting loose and limber, sometimes more than once during the course of the game. He might stretch, run, ride a stationary bike, and of course, take some cuts.

The quantity and type of those swings depend on individual preference. Stairs, for example, estimates that he averaged close to 500 hacks per day, and almost all of those came before first pitch.

“My game was my batting practice,” Stairs said. “Nobody could take that away from me, so that’s when I’m really going to have fun and see how many home runs I can hit and how far I can hit a ball and just have some fun with it."

Stairs didn’t bother to work the whole field with line drives. His goal was to go deep on every pitch, picking out the most remote deck in any particular stadium and trying to reach it with “bazookas.”

Others take time before and during games to utilize the batting cages situated near the dugouts in most stadiums. They take cuts off a tee, at tosses from a coach or against a pitching machine.

With the Nationals trailing the Reds, 2-1, in the ninth inning of a May 19 game in Washington, veteran Nats reserve Scott Hairston knew he could be headed toward an encounter with flamethrowing Cincinnati closer Aroldis Chapman.

Hairston, the active leader with 13 pinch homers, went to the cage and had a coach pull the protective screen to within about 40 feet of the plate before firing pitches at him to simulate the velocity Chapman unleashes from 60 feet, 6 inches.

Sufficiently geared up for Chapman's missiles, Hairston got his bat on a 99-mph, two-strike fastball at the letters and lofted it to left for a game-tying sacrifice fly.

It had been several hours since Hairston arrived at Nationals Park, and his game action lasted all of two minutes. That's an equation destined to provoke frustration, but this time, it produced a critical run.

"A lot goes on -- more than people think -- preparing for what we do," Hairston said.

-- Andrew Simon writes for MLB.com. You can follow him on Twitter @AndrewSimonMLB.