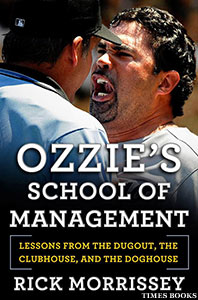

Ozzie Guillen managed his last game for the Chicago White Sox on Sept. 26, 2011. Now, when he's not serving suspensions for ill-conceived statements about Fidel Castro and his longevity, he mans the top step of the dugout in Little Havana as manager of the new-look Miami Marlins. As was the case in Chicago, Miami will never be the same once it has been "Ozzified." Rick Morrissey, an award-winning sports columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times, reveals the strategy and psychology that underpin the fiery manager's antics in Ozzie's School Of Management: Lessons from the Dugout, the Clubhouse, and the Doghouse This excerpt is from the chapter titled "Protect Your Employees From The Barbarians."

Ozzie Guillen's modus operandi is as obvious as Day-Glo: Take all the negative attention off a struggling player or a struggling team and put it on himself. Let him rise up to all of his five-foot-eleven frame and absorb the blame. Please let him. He lives for it. There is something at once generous and comical about the way he jumps on grenade after grenade for his players. The man collects shrapnel like some kids collect baseball cards. He wouldn't trade it for the world.

"Give me the pressure," he said. "I'll take the pressure. I take the heat. Let the guys play. Let my players play. Anything that's negative, I take it. I want to take all the heat. I want to take all the pressure myself, and hopefully I can handle it."

Ozzie Guillen, human shield.

After losing a game to the Toronto Blue Jays in 2008, his team's sixth straight loss, Mount Guillen erupted in front of the media. It was a calculated explosion, meant to take the pressure off his players and to inform them that when God divvied up the sides, He decided it would be the White Sox against the world.

Amid all the sarcasm in his outburst, Guillen somehow managed to weave in his distaste for the Cubs' hold on the city of Chicago. That's called "multitasking," class.

"We won [the World Series] a couple years ago, and we're --------," he told reporters. "The Cubs haven't won in 120 years, and they're the -------- best. ---- it, we're good. ---- everybody. We're --------, and we're going to be --------- the rest of our lives, no matter how many World Series we win. We are the bitch of Chicago. We're the Chicago bitch. We have the worst owner -- the guy's got seven -------- rings, and he's the -------- --------- owner."

The White Sox went on to win twelve of their next seventeen games.

"There's a method to his madness," said White Sox pitcher John Danks. "Whenever we need the attention taken off us or if he needs to do something to loosen us up, I think Ozzie knows what he's doing. Ozzie's a character, no doubt, but there have been times when he's said things or done things where it's almost planned."

Are his efforts meant to protect the players or to bring attention to the manager? It's the debate about Guillen that won't go away. What's not up for debate is whether he likes it or not. Managers forever have tried to take pressure off their teams by deflecting criticism that might otherwise barrel into their players. Few have enjoyed doing it as much as Guillen has.

So, heat? Oh, goodness, bring it on. Heat will never get a warmer reception than the one Guillen will give it. He talks almost giddily about the heat. Heat is a respected opponent. It has flesh and bones, body and soul, and it and him are in a cage match. A huge crowd is watching, which is part of the allure.

"Pressure?" he said. "Never. Never. Never. You know what's pressure to me? My dad. He's broke down in Venezuela, waiting for me to send the paycheck every fifteen days. That's pressure.

"Me? I'm fine. I love the heat. I love the heat. I don't hide from anybody. I like to be in the hot seat. If they don't play good, I should be fired. If they play good, they should keep me. That's the way it is.

"I never feel pressured by any circumstances. Never. Never. In my life, when I was a kid. Now that I'm a grown man, I know what I can do. I have a lot of confidence in myself, a lot of confidence in my coaching staff. That's the reason they spent a lot of money on this ball club and give it to me -- because they have confidence in me.

"They can fire me and give the ball club to somebody else. No. I'm very comfortable where I am right now. Very comfortable."

Those thoughts came hours before the White Sox' 2011 season opener in Cleveland, which would seem like an odd time to be talking about job termination. But when you walk with Ozzie, all roads lead to this topic. It's his favorite mode of deflection, though he would never admit it. Several times a month in each baseball season, he brings it up unbidden. Even in 2005, when he won a World Series, he talked about going to live on his boat near his off-season Miami home if Reinsdorf decided that he, Guillen, was no longer capable of doing the job.

There are certain givens in life. Death. Taxes. The sun setting in the west. And Ozzie Guillen at some point saying the owner should fire him if the team is doing poorly. This will happen with the Marlins, too. The only question is how soon.

It is his tried-and-true way of protecting his players in tough times, but it also comes from his need to take responsibility. It's something he had decided on as a fourteen-year-old who was all but living on his own in Venezuela. He would try not to blame anybody else for his own failures. He would carry any burden presented to him, in addition to the one already on his back. It's why he took responsibility over and over for the White Sox' poor season in 2011.

Whenever Guillen talks about getting fired, it tends to suck up all other discussion, the way a black hole sucks in everything around it. It came in handy a little more than a month into the 2011 season, when the Sox were bad. Not just standard-issue bad, but bad beyond belief. Exquisitely bad. Cover-your-eyes bad. They had the worst record in baseball.

But this time, the subject of his getting fired was not just another arrow in his quiver of motivational tools. The calls for his head were loud and getting louder. They were on radio sports talk shows. They were on Internet discussion boards. Guillen heard them and read all about them, even though he claims he ignores media reports about his team.

On May 7, baseball writer Phil Rogers of the Chicago Tribune led off a column with the reasonable assessment that firing Guillen wasn't going to solve the Sox' problems. But while Rogers was at it, he listed sixteen possible replacements if the team canned its manager. That's the climate Guillen found himself in. Few people in Chicago believed Reinsdorf was going to send Ozzie to the managers' graveyard, but no one seemed averse to kicking the tires on a hearse, just in case. The temptation was to describe all the losing as a Greek tragedy, but nobody had died and a Trojan horse filled with .300 hitters hadn't arrived. Help was not on the way.

So now Guillen was rummaging through his bag of tricks to rejuvenate his team, to kick some ass, to get the critics off his players' backs, to divert attention from a club that was shockingly awful. He went where he always goes, to his thoughts of being fired.

"At this point, I don't trust anyone," he said of his job status. "Do you think Jerry is going to come to me and say, 'Listen, we might fire you'? What do you think I'm going to say? No? Hey, man, you've got a lot of reasons to do it. How many games have we lost? Twenty games already? You have 120 million reasons [dollars] and you have thirty reasons [players and coaches] about why we're not winning. You think I'm going to tell Jerry don't do it? No."

The night before, he had watched his team hit rock bottom, which wasn't as bad as it sounds. At least it had hit something. Minnesota Twins pitcher Francisco Liriano had come into the Sox' offense-friendly ballpark and thrown a no-hitter, despite the fact he had brought with him a 1–4 record and a fleshy 9.13 earned-run average. It wasn't as if Liriano had been sharp that night. He had walked six batters.

But the White Sox, who had entered the season believing they were going to be contenders for the American League Central title, couldn't have hit a metal baseball if they were swinging magnetic bats. Their $127 million payroll, fifth highest in Major League Baseball, had raised huge expectations on the South Side of Chicago, and perhaps the Sox were feeling the full weight of those hopes and those dreams and those dollars.

Everyone had been expecting Guillen to erupt. They had been looking for signs of seismic activity. There had been a few rumbles but nothing large. He said privately that an eruption was the last thing his players needed at that moment. To send up fire and ashes so early in the season would be a sign he was panicking. And if he panicked, he believed, his players would follow suit.

The players, on the other hand, were ready for anything from their leader.

"With Ozzie ... it's kind of like the Tasmanian devil, where you don't know," said middle reliever Will Ohman. "His reactions sometimes are unexpected. But you know what you're going to get. You don't know when you're going to get it, but you know what you're going to get."

The "when" arrived near the end of May. Guillen might have believed with all his heart that this was a time for him to act presidential and not like a general leading an amateurish coup. But, well, all the losing was beyond his ability to control himself.

The eruption was vintage Ozzie, full of volcanic debris, misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and general confusion. It was sound and fury signifying something, though afterward witnesses would huddle together to try to make sense of what that something was.

It came after a fourteen-inning loss in Toronto on May 28 and carried over into the next day like a stalled weather system. Guillen cleared his throat. It was like a maestro picking up his baton. The tongue unfurled. He ripped the team. The next day, he seemed to rip the fans. Then he ripped the media for saying he had ripped the fans.

What set him off initially was his team's failure to take advantage of scoring opportunities in the game, especially in the late innings. He had done his best La Russa imitation, trying to create something out of nothing strategically. He had used Gavin Floyd, a starter, in relief. He had put Omar Vizquel at first base for the first time in the infielder's long career.

That improvisation had earned him some criticism. Ozzie played Vizquel where? Why was young reliever Chris Sale allowed to stay in the game for a career-high three innings?

As is often the case with Ozzie, no one was exactly sure where he had heard the criticism. Sometimes he gets bits of information from friends and family who read the papers or listen to the talk shows. Other times, he expands one fan's unhappiness into general public dissatisfaction. A few tweets turn into what he perceives as a flock of abuse. There is criticism he sees and some he imagines. He insists it doesn't bother him when someone questions his baseball acumen.

This time, it really didn't matter where the criticism had originated. What mattered was that it had reached Guillen in Toronto after that fourteen-inning loss to the Blue Jays. The spark had grown up to be a forest fire.

The next day, he talked with reporters about the thankless job coaches have. He talked about a general lack of appreciation for coaches. He said his life would be so much easier and so much less stressful if he didn't care so much for the White Sox organization. And, of course, he used the F word. No, no that one. This one: Fired.

"People only care when you lose games: 'He should get fired,' " he said. "When we win games, they say, 'Those guys are great players.' "

If this was Calculating Ozzie, he was doing a great job of acting. It more likely was Hurt Ozzie. It's one of the contradictions about him. He gladly takes the abuse in order to protect his players, but he's still stung by that abuse. In his lengthy discussion with the media, he envisioned what it would be like for the organization to honor him, the coaching staff, and the players before a game many seasons in the future.

"Are they going to feel sorry because we're going to get fired? ---- no," he said. "They only remember us from 2005. In 2020, we'll come here in a wheelchair all ------ up. As soon as you leave the ballpark, they don't care about you anymore. They don't. The monuments, the statue they got, they pee on it when they're drunk. That's all they do. Thank you for coming, bye-bye. Thank you for coming for thirty minutes for all the suffering you did all your life, day in and day out."

This is where the parsing started. Who was this "they" to whom Ozzie referred? It seemed to be White Sox fans. Who else gets drunk at baseball games? Certainly not the media, though Guillen might argue it would improve the writing and reporting ability of many a reporter.

When his words showed up in news stories online, he became incensed that some reporters had interpreted them as a slam on the fans. He claimed he meant that critics in the media, not Sox fans, would piss on players' and managers' statues.

He fully understood what it would look like if he were ripping the fans who buy the tickets. He had always held himself up as a man of the people, a person willing to speak his mind like every other hardworking guy on the South Side of Chicago. It is part of his charm. He had completely bought into Sox fans' caricature of Cubs fans as being less interested in baseball than in partying at Wrigley Field.

So for him to take a swipe at Sox fans for being ungrateful would have been harmful to the reputation he had built for himself. He started tweeting like mad.

"They should print everything I said ... that was low blow and irresponsible...no class...Bunch a crap...No mention any fans and alcohol."

The Sox issued a statement that sounded more like George Will's bow tie talking than Ozzie Guillen's lips: "If anyone listens to the entire conversation or reads a transcript of what I said, they will see my comments were not directed as criticism of White Sox fans."

The result of all the turmoil? There was zero attention on the players and the losing. Oh, and the White Sox went to Boston and swept the Red Sox. The team seemed to feed off Guillen's emotions, which, bottom line, is the whole point. Take the attention away from the flailing team. Throw your body on the incendiary device. Never mind that you're the one who threw the bomb in the first place. By the time it's over, no one will remember that detail.

"I'm getting criticized every day in my life," Guillen said. "People say, 'What the ---- are you doing? Why don't you hit and run, why don't you bunt?' That's my life. That's why this ------------ thing [slapping himself on the back] is very strong. I've been criticized all my life. I don't give a ----. I'm strong. I face the media with my head up."

But why does he put himself through it? Why not try to ignore the tweets, the newspaper columns, the talk shows?

"I don't give a ----," he said. "I really don't care. Those guys out there that are -------------- me? I was a great manager for eight -------- innings earlier in the season. All of a sudden a guy drops a ball and we give up a run and I'm a piece of ----.

"To be honest with you, I'd rather have the fans be in my ass and criticize me. I want the fans and the media to criticize me and stay away from my players. If you want to know something about my players, I'll be honest. When the media and the fans get on the players because your manager's not honest, the media knows it's --------. I learned that as a player.

"I'd rather say, 'This is the way it is. I'll take the blame.' I'm the one who made the decision. I'm the one who thought this is going to be good for the team. This guy failed? Blame me because I'm the one who made that move."

It takes a certain kind of person to absorb abuse, to want to absorb it, to actually seek it out for the purpose of staging a head-on collision. The Toronto blowup was mostly Guillen's creation, helped along by what he called a misinformed media.

What kind of person puts himself through this?

"Deep down I think he likes it," A. J. Pierzynski said. "I don't know if he'd ever admit that. You'd have to like it a little bit, otherwise you wouldn't do it. He loves the attention. He's had a great career because of it. He brings focus to the White Sox and focus to the South Side, and it's not a bad thing all the time. I think he does a good job with when to do it and when not to do it."

Dan Gladden, the Twins radio analyst and a former Minnesota player, would later go on WSCR radio in Chicago and cut to the heart of the debate about Guillen in the baseball world.

"What Ozzie does well is he deflects the criticism from the players, and I think every good manager does that," Glad- den said. "That's why he'll have those outbursts and some embarrassing moments at times. He's deflecting the criticism from the players, and it's on him. But at the same time, it's almost like enough is enough. It gets old. We've heard this, we've seen this before. Keeping guys loose in the clubhouse ... let the players dictate and decide what kind of a clubhouse they want. It shouldn't be decided by the manager. He's won a World Series -- you can't take that away from him -- but I think it'd be distracting as a player."

Several days later, sitting in the dugout before a game, Ozzie feigned ignorance.

"Who's Dan Gladden?" he said. "Who's that? If that ---- came from [Hall of Famer and Twins broadcaster] Bert Blyleven, I'd say, 'Wow. ---.' But Dan Gladden? That's a pimple on my ass."

-- Excerpted by permission from Ozzie's School Of Management by Rick Morrissey. Copyright (c) 2012 by Rick Morrissey. Published by Times Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- 'Juice' Survives The Streets To Become Marlins' Barber To The Stars

-- The Walk-On: Matt Stewart's Inside Story Of Northwestern's Rise To Big Ten Champs

-- Which Sports Conspiracy Theory Can You Believe?

-- The Hottest Fitness Trend You've Never Tried