A lifelong football fan, Steve Almond also struggles to support a sport whose participants are afflicted with lifelong pain and suffering. In Against Football, Almond asks a wide range of questions about America's favorite sport, and he follows their answers to often-disheartening conclusions. By the end, Almond realizes he can no longer set his morals aside to enjoy a sport that produces so may victims. Here is ThePostGame's exclusive interview with the author.

ThePostGame: Can you look back and see a moment where you were first aware of the internal conflict of watching football?

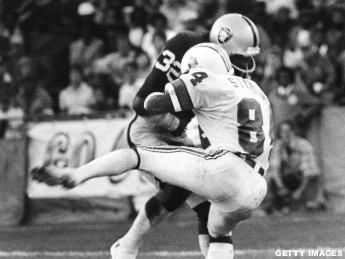

STEVE ALMOND: I write about, as an 11-year-old kid, watching Darryl Stingley get paralyzed. He was a New England wide receiver, and by then I was already a devout Oakland Raiders fan for several reasons: to be close to my dad, to have an appropriate and heroic outlet for male aggression. Seeing a player paralyzed before my eyes, my immediate thought was that his body wasn't moving and it was in a very eerie shape. My central memory as I have preserved it in my mind is that I was afraid. I had the logic of a child, and my logic was, 'Oh my god, this guy just got paralyzed, they'll have to stop playing football.'

I remember thinking, 'Wow, they're just going to go on, and he's clearly paralyzed.' But of course, my identification was with Jack Tatum, the assassin who delivered the hit. I didn't feel bad about Stingley complicitly as a fan, I felt bad that this beautiful game I cared about so much wasn't going to be played any more. I feel even worse looking back on that, that my thoughts weren't about Stingley, they were about not being able to watch football.

I think over the past decade, maybe I realized that there's some kind of unholy allegiance to this game, if I really examine it. It's not just the positive stuff, seeing greatness, seeing athletic brilliance. ... That stuff's all true, but there's a reason I was deeply drawn to football and not baseball or swimming: because there is violence in it.

When I go to watch football, it isn't with the same values I hold outside of football. The truth is [my change-of-heart was] like the Great Depression: When you ask, "How did you go broke?" people say, "A little at a time and then all of a sudden."

TPG: When did you make the decision to write a book on the subject?

ALMOND: In the last chapter, I essentially try to answer that question. [The answer is] really after seeing my mom suffer from acute dementia. Basically, she went from being a functioning doctor, psychoanalyst to being gone, being in a delirium. I flew out to Palo Alto and walked into this intensive care unit and my mom was gone. She didn't know where she was; most of the time, she didn't know who I was. She thought she was in the middle of a horrible dream.

That was the moment were it was like, holy shit, this is the same thing that happens to football players. The stories about suicide and depression, that's kind of an abstraction. ... You make the necessary excuses, and it remains abstract. When I saw my mom and walked into the room, it was a real thing and it was suddenly much harder to compartmentalize football morally. I would think, "Hey, I'm watching a game where the end result is what's in this hospital room." … I think that was the moment where I was like, "Okay, I have got to revisit this."

Once I started doing that, it was just much darker than I realized. Things I never really thought about, how [football] affects the educational mission of this country, how it hurts local economics, other nihilistic elements of this game -- I just hadn't thought about deeply.

TPG: A lot of press about football focuses on tangible things within the game: concussions, violence, aggression, etc. You focus on the harder-to-quantify fan relationship. Why is this perspective important to the larger conversation about football?

ALMOND: I think that with fans, there's a whole media engine that's in place. The NFL has its own propaganda machine, and it's a very good propaganda machine. The same for the NCAA: [the proposition] is basically, "We'll present such a thrilling spectacle that you, the fan, will not bother to look at the moral hazards of the game." It gives fans so much pleasure, they have no interest in examining the moral conflicts.

What I'm doing [with Against Football] is disruptive in a way. Football is amazing, it is a spectacle, but it's also all these other things. The way I have to suppress my empathy -- I knew that didn't line up with me in other parts of my life.

You mostly treat sports in general, and football specifically, as a form of entertainment. Fans don't see it as a workplace. They don't ask, "What does it mean that three out of 10 employees are going to end up with long-term cognitive problems?"

Football is the biggest unifying narrative we have in America, bigger than religion. In terms of how much we give to the game, how much of our minds and our wallets, nothing is bigger. But for years we haven't looked at football as a moral undertaking. Only in the past five or six years have fans been asked to consider whether what they are involved in is corrupt.

TPG: In the prologue you say that football, at its best, is a "highly intricate form of art." Do you think there's any way to reform the game while preserving those artistic qualities?

ALMOND: That's the $64 billion question. Yes, I do. In fact, at the end of my book I put forward some suggestions. Football is like capitalism on steroids: it's all about winning and losing, but mostly winning. The only thing that matters is that you win, and once you win, you get paid. Winning is what makes you feel like you paid off.

That's what you see with this kid [quarterback Shane Morris] at Michigan, [coach Brady Hoke] is sending him back in because he's sitting there saying, "Hey, I'm coaching for my job, we need to win this game." There are many things that would help preserve the game. The first one is weight limits. One of the things that's happened in football is players just keep getting bigger. It's just simple physics, it's mass times acceleration. If you force a coach to say, "Okay, we've got 4,000 pounds to work with and you can't go over," you can help keep kids at their natural playing weight and prevent some of these head injuries.

Another thing is putting monitors in the helmets of players so that once they hit a certain [amount of accumulated impact], they have to be pulled from the game. Coaches would have to say, "Hey, you can't keep going with your head first, you've got to find another way to wrap up, because if you get in another collision I have to pull you out of the game." It's not just the concussions to worry about, it's these sub-hits, these little car crashes that rattle the brain.

I think ultimately, my book is saying not to boycott the game, not to ban the game, but to … help people feel a moral conflict and then make their own decision.

TPG: Football may be art. But like many forms of art, it takes a lot of understanding to be fully appreciated. It's possible that most people won't engage with its complexities enough to understand its beauty beyond the superficial features. What would you say?

ALMOND: I think that people come to football for all different kinds of reasons. I think one of the things my book is doing is trying to ask, "Why are you drawn to it?" For me, it was my dad and as a way of getting close to him. But it's also because my friends watch it together and it's very fun. Some reasons are very laudable, like we just want to see greatness. There's nothing wrong with that, seeing greatness on display.

The problem is the thrill of the violence. It's like watching gladiators. Football really plugs us into this primal sense of aggression, being heroic, and it's always served that function. America has always re-energized itself off of violence. Football is plugging into something very ancient in the American spirit. People love it. I did for many years, and I still do. I think casual fans are attracted to it because everyone in their town, their friends, are into it, and they want to be included, they don't want to be on the sidelines.

TPG: Despite all the bad press about Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson, the NFL's TV ratings emerged unscathed. Is this a case of people not caring enough to make a change, or could those seeds be taking root, and people just aren't ready to commit to taking action?

ALMOND: I think probably both of those scenarios. My book is disruptive. It's trying to start something. Rather than holding the fans accountable, what the pundits say is that Ray Rice, that Roger Goodell, they're the scapeboats. If we get rid of the bad apples, we're going to be fine. Fans don't want to be implicated. … They say that a player or owner is so greedy, but they don't say, "Hey the NFL is this engine of greed, it's an immoral industry, somehow tax-exempt, it's never going to have a conscience."

People feel bad for a while, they tsk-tsk, and then they go back to watching. They haven't had a serious discussion. I fear it's never going to happen, but that's what my book is trying to do. Let's also recognize the price we pay: Not just the players, but also the communities ripped off and extorted by the NFL, and also the empathy that we suppress, [passively endorsing that] women are sexual instruments, men are all masculinity ... no one questions that men are dominant and women are on the sidelines.

Moral progress is possible. It's hard, but we can do it.

TPG: You've said you're going to try not to watch any football this season. How's that going so far?

ALMOND: Kind of shitty. In other words, I'm not watching it, and I miss the time I spent with my friends. [Football] is hard to get away from. I guess it's like being a drunk: once you leave something, only then do you realize how ubiquitous it is.

When I watch -- when I catch [a game] for a second, what I notice is the players' heads. I'm watching it differently. ... I'm not watching with the mindset of who's winning, I'm wondering, 'Oh my God, I hope that kid's brain is alright.' And that will take the romance out of a fourth-quarter drive real quick.

-- Against Football by Steve Almond is published by Melville House. It is available for purchase from the publisher, Powell's, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Steve Almond on Twitter @stevealmondjoy.