Russell Armstrong succeeded. He had a sinewy blonde wife, piles of cash, and a sprawling residence in the 90210. And oh my God, he was on a reality television show! A paid role in a vapid horror show like The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills is the Holy Grail of American existence in the 21st century. Before filing for divorce, Armstrong’s wife called him "a man's man." And he was very much that in the sense he possessed all the things that please other men. But it wasn’t enough to keep him from hitting his wife or hanging himself.

Did you know Ernest Hemingway was a man's man too? Running with the bulls in Pamplona, fishing for marlin in Mexico, and scaling Kilimanjaro wasn't just the stuff of literary inspiration; it was a lifestyle. Hemingway fancied himself an amateur boxer and in between manuscripts he was known to challenge people to impromptu duels.

Hemingway scholars like to drone on about his preoccupation with the "idealized self." It's a neurotic condition by which a person endows himself with "exalted faculties." The individual becomes "a hero, a genius, a supreme lover, a saint, a god." Hemingway has been taken to task for foisting these attributes onto many of his characters who are thought to resemble him. But as Hemingway's own life ended with a shotgun blast by his own hand, there's not much evidence to suggest he saw himself as anything but spectacularly flawed.

An idealized version of one self defines the American Dream. After all, the idealized version of you is what you see when you peer into the mirror of one your 10 bathrooms in your palatial digs in your gated community that is reserved for those who "work hard" enough to get it, right?

But it seems the Dream is quite hazardous these days. Whether you're a baring your tortured soul in Beverly Hills, or scaling fences in Tijuana, tunneling under walls in Nogales, or cruising over the border in Laredo while doing your best imitation of cargo in the flatbed of an 18-wheeler, the pursuit of the Dream may prove costly. Even those make it, like Armstrong, are haunted by the specter of ultimate failure -- losing it all.

But Armstrong always succeeded. So when he wanted out, he successfully made his exit.

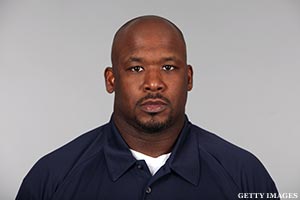

Corwin Brown is, fortunately, a little different. He played football in high school, then at Michigan and for the Patriots and Jets. He played well, too. Then he coached. And Brown did that well, too, becoming a college defensive coordinator at the young age of 37. This doesn't happen very often for men who look like Brown.

But then something took hold of the man. Perhaps it was something that had been there all along, and lay dormant until the conditions were just so. Perhaps it was there long before he ever pulled on his first set of shoulder pads or heard that sweet sound a chin strap makes when it's buckled to a helmet. But on August 13, Brown grabbed his wife and dragged her into their home. He then held her hostage by gunpoint. When police arrived, he held them at bay for seven hours. When he finally emerged, blood poured from a self-inflicted wound.

We know Brown was charged with one count of domestic battery and two counts of felony confinement. But we don’t know his motive.

Whatever the evidence may provide, Brown failed. He failed to keep his cool, he failed in his efforts to restrain from putting his hands on his wife. And after that standoff with police, he failed to kill himself. This, on the surface, is what separates Brown from Armstrong.

Of course Corwin Brown's hands on a woman means something different than Russell Armstrong's hands on a woman. Armstrong was apparently stressed out by the pressures of being a bookie, er ah ... venture capitalist, and from being on television.

Brown is a muscular man who was accustomed to being on television. And everyone knows athletes don't get stressed out, because that term suggests an evolved existence. In the sorting of complicated organisms, athletes fall just short of amoebas, so the response to an athlete’s troubles is something predictably formulaic. It’s either a sense of entitlement: "athletes hit women because they think they can do whatever they want to whom whatever they want." Or it’s just an issue of identity. "They simply struggle with real life after football." This seems to be the pervading theory anyway. It’s not my theory, mind you, but I know how these things are presented.

So it comes as little surprise that Corwin Brown’s family, in the heartbroken search for answers, has turned to the football-had-something-to-do-with-it-theory. They attribute his assault on his wife and attempted suicide to complications from playing football. They wonder if years of high-impact collisions led to Brown beating his wife and holding her hostage. They wonder if what plagued Brown is what felled Dave Duerson.

This makes sense. You know why it makes sense? Because football makes sense. Like everything else organized by human hands, certain aspects of sport are infected by the virus of politics. But whatever happens on the grass every Sunday afternoon is true. So everything related to that game must also be true.

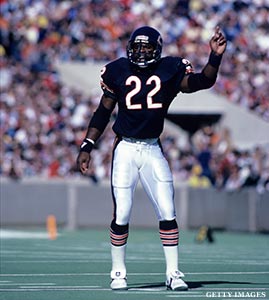

Dave Duerson thought this. Talk about a man's man. Duerson was a member of that '85 Bears defense. 'Nuff said.

But Duerson was also troubled. When he needed answers for why he had lost the will to live, he went back to what had been the source of life -- 'ball. He'd suffered ten concussions. Surely there was a price for that. Surely those few times he lay completely blacked out on the field had some residual effect on his being. Turns out Duerson was right in one sense. After he shot himself in the chest, it was discovered that he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a disorder linked to repeated brain trauma.

But does that explain everything? Does it explain what happened to Brown? I wish it did. If Troy Aikman or Steve Young were to become suicidal, heaven forbid, I might be more willing to accept the formula. I wish there were a quick and easy formula to solve the mystery of depression -- especially among athletes. But there isn't. Not yet anyway. Besides, there are plenty of men who've never lost consciousness on the field, who in pursuit of some elusive ideal, still fall headlong into the abyss.

Whatever dreams may come in death, I hope they aren't as painful as those realized in life. And after he emerges from whatever form of incarceration awaits him, I hope Corwin Brown will pursue his next dream because the one he had is over. There will be questions aplenty, especially from his children. And in time there may even be some answers. That's only because Corwin Brown, unlike Russell Armstrong, is still here.

-- -- Alan Grant played cornerback for the Colts, 49ers, Bengals and Redskins. He is the author of

"Return to Glory: Inside Tyrone Willingham's Amazing First Season at Notre Dame."